Chapter 5. Syntax-Driven Translation

5.1 Introduction

Fundamentally, the compiler is a program that reads in another program, builds a representation of its meaning, analyzes and improves the code in that form, and translates the code so that it executes on some target machine. Translation, analysis, optimization, and code generation require an in-depth understanding of the input program. The purpose of syntax-driven translation is to begin to assemble the knowledge that later stages of compilation will need.

As a compiler parses the input program, it builds an IR version of the code. It annotates that IR with facts that it discovers, such as the type and size of a variable, and with facts that it derives, such as where it can store each value. Compilers use two mechanisms to build the IR and its ancillary data structures: (1) syntax-driven translation, a form of computation embedded into the parser and sequenced by the parser's actions, and (2) subsequent traversals of the IR to perform more complex computations.

Conceptual Roadmap

The primary purpose of a compiler is to translate code from the source language into the target language. This chapter explores the mechanism that compiler writers use to translate a source-code program into an IR program. The compiler writer plans a translation, at the granularity of productions in the source-language grammar, and tools execute the actions in that plan as the parser recognizes individual productions in the grammar. The specific sequence of actions taken at compile time depends on both the plan and the parse.

During translation, the compiler develops an understanding, at an operational level, of the source program's meaning. The compiler builds a model of the input program's name space. It uses that model to derive information about the type of each named entity. It also uses that model to decide where, at runtime, each value computed in the code will live. Taken together, these facts let the compiler emit the initial IR program that embodies the meaning of the original source code program.

A Few Words About Time

Translation exposes all of the temporal issues that arise in compiler construction. At design time, the compiler writer plans both runtime behavior and compile-time mechanisms to create code that will elicit that behavior. She encodes those plans into a set of syntax-driven rules associated with the productions in the grammar. Still at design time, she must reason about both compile-time support for translation, in the form of structures such as symbol tables and processes such as type checking, and runtime support to let the code find and access values. (We will see that support in Chapters 6 and 7, but the compiler writer must think about how to create, use, and maintain that support while designing and implementing the initial translation.)

Runtime system the routines that implement abstractions such as the heap and I/O

At compiler-build time, the parser generator turns the grammar and the syntax-driven translation rules into an executable parser. At compile time, the parser maps out the behaviors and bindings that will take effect at run- time and encodes them in the translated program. At runtime, the compiled code interacts with the runtime system to create the behaviors that the com- piler writer planned back at design time.

Overview

The compiler writer creates a tool--the compiler--that translates the input program into a form where it executes directly on the target machine. Thecompiler, then, needs an implementation plan, a model of the name space, and a mechanism to tie model manipulation and IR generation back to the structure and syntax of the input program. To accomplish these tasks:

- The compiler needs a mechanism that ties its information gathering and IR-building processes to the syntactic structure and the semantic details of the input program.

- The compiler needs to understand the visibility of each name in the code--that is, given a name , it must know the entity to which is bound. Given that binding, it needs complete type information for and an access method for .

- The compiler needs an implementation scheme for each programming language construct, from a variable reference to a case statement and from a procedure call to a heap allocation.

This chapter focuses on a mechanism that is commonly used to specify syntax-driven computation. The compiler writer specifies actions that should be taken when the parser reduces by a given production. The parser generator arranges for those actions to execute at the appropriate points in the parse. Compiler writers use this mechanism to drive basic information gathering, IR generation, and error checking at levels that are deeper than syntax (e.g., does a statement reference an undeclared identifier?).

Chapters 6 and 7 discuss implementation of other common programming language constructs.

Section 5.3 introduces a common mechanism used to translate source code into IR. It describes, as examples, implementation schemes for expression evaluation and some simple control-flow constructs. Section 5.4 explains how compilers manage and use symbol tables to model the naming environment and track the attributes of names. Section 5.5 introduces the subject of type analysis; a complete treatment of type systems is beyond the scope of this book. Finally, Section 5.6 explores how the compiler assigns storage locations to values.

5.2 BACKGROUND

The compiler makes myriad decisions about the detailed implementation of the program. Because the decisions are cumulative, compiler writers often adopt a strategy of progressive translation. The compiler's front end builds an initial IR program and a set of annotations using information available in the parser. It then analyzes the IR to infer additional information and refines the details in the IR and annotations as it discovers and infers more information.

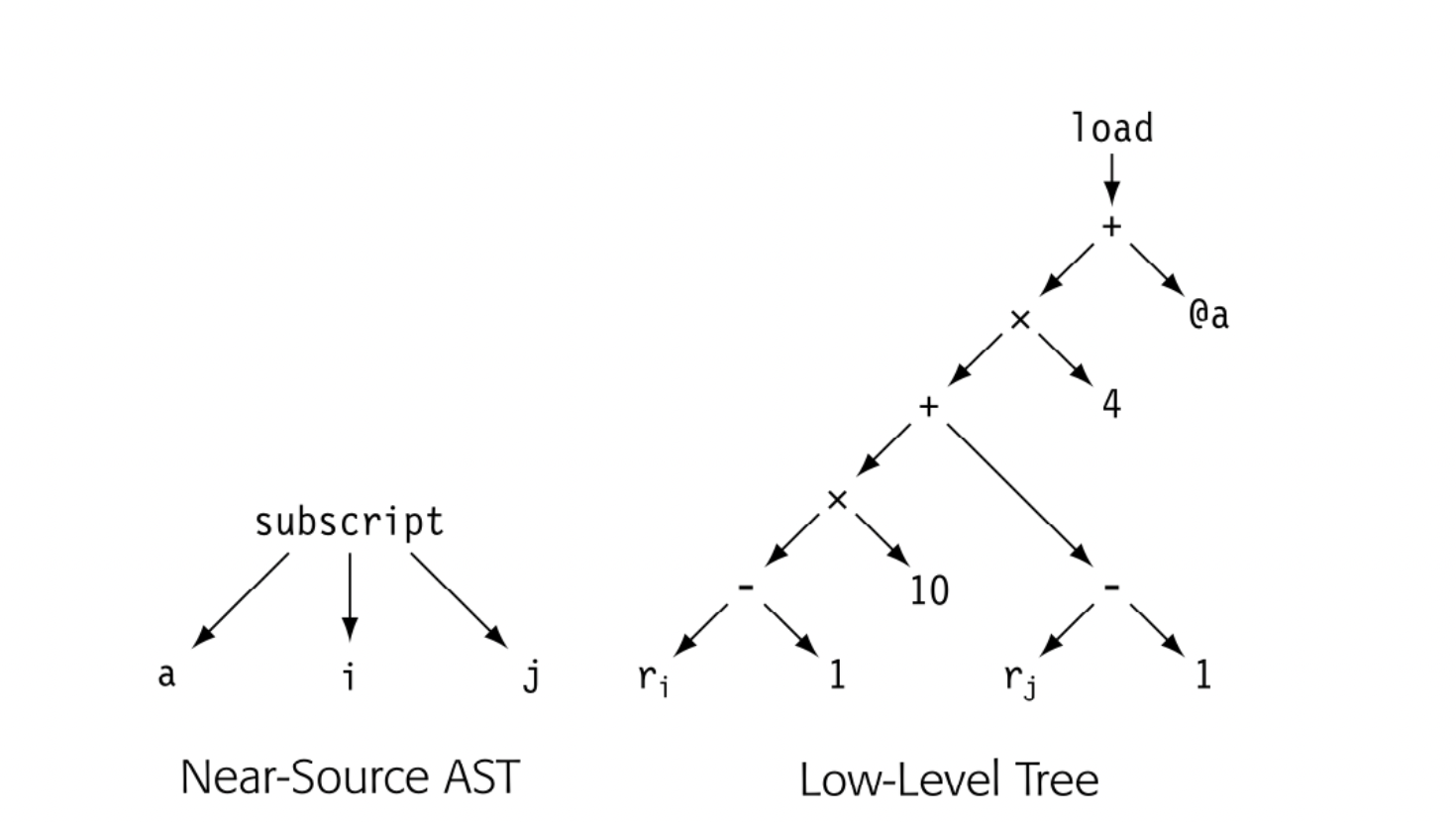

To see the need for progressive translation, consider a tree representation of an array reference . The parser can easily build a relatively abstract IR, such as the near-source AST shown in the margin. The AST only encodes facts that are implicit in the code's text.

To generate assembly code for the reference, the compiler will need much more detail than the near-source AST provides. The low-level tree shown in the margin exposes that detail and reveals a set of facts that cannot be seen in the near-source tree. All those facts play a role in the final code.

To generate assembly code for the reference, the compiler will need much more detail than the near-source AST provides. The low-level tree shown in the margin exposes that detail and reveals a set of facts that cannot be seen in the near-source tree. All those facts play a role in the final code.

- The compiler must know that a is a array of four-byte integers with lower bounds of 1 in each dimension. Those facts are derived from the statements that declare or create a.

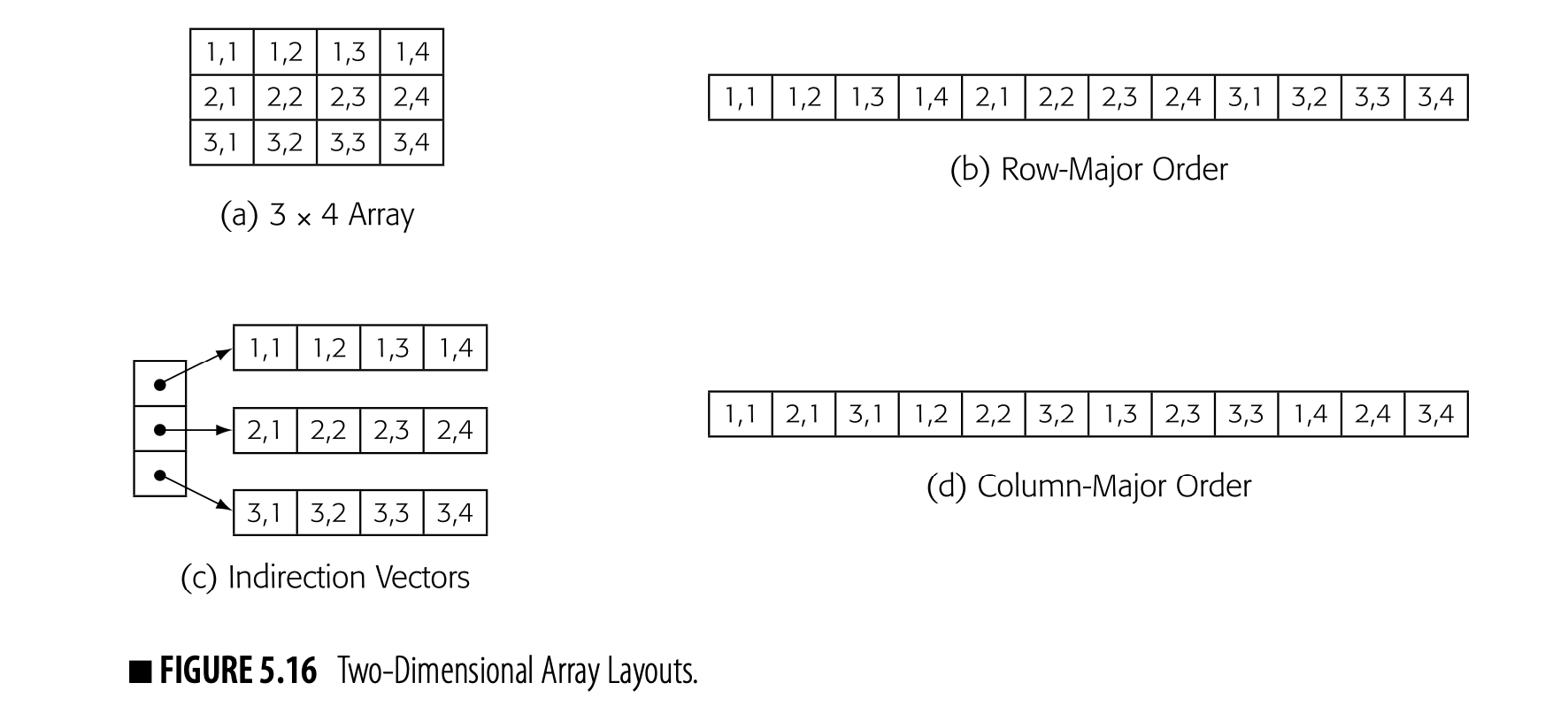

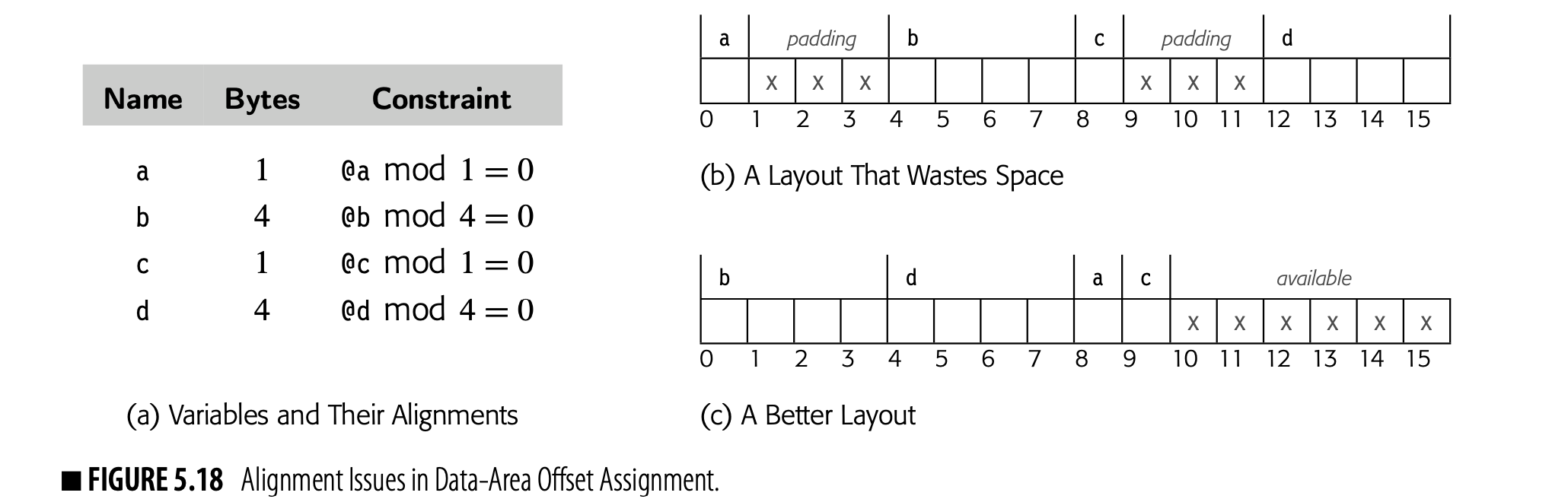

- The compiler must know that a is stored in row-major order (see Fig. 5.16). That fact was decided by the language designer or the compiler writer before the compiler was written.

- The compiler must know that @a is an assembly-language label that evaluates to the runtime address of the first element of a (see Section 7.3). That fact derives from a naming strategy adopted at design time by the compiler writer.

To generate executable code for a[i,j], the compiler must derive or develop these facts as part of the translation process.

This chapter explores both the mechanism of syntax-driven translation and its use in the initial translation of code from the source language to IR. The mechanism that we describe was introduced in an early LR(1) parser generator, yacc. The notation allows the compiler writer to specify a small snippet of code, called an action, that will execute when the parser reduces by a specific production in the grammar.

Syntax-driven translation lets the compiler writer specify the action and relies on the parser to decide when to apply that action. The syntax of the input program determines the sequence in which the actions occur. The actions can contain arbitrary code, so the compiler writer can build and maintain complex data structures. With forethought and planning, the compiler writer can use this syntax-driven translation mechanism to implement complex behaviors.

Through syntax-driven translation, the compiler develops knowledge about the program that goes beyond the context-free syntax of the input code. Syntactically, a reference to a variable is just a name. During translation, the compiler discovers and infers much more about from the contexts in which the name appears.

-

The source code may define and manipulate multiple distinct entities with the name . The compiler must map each reference to back to the appropriate runtime instance of ; it must bind to a specific entity based on the naming environment in which the reference occurs. To do so, it builds and uses a detailed model of the input program's name space.

-

Once the compiler knows the binding of in the current scope, it must understand the kinds of values that can hold, their size and structure, and their lifetimes. This information lets the compiler determine what operations can apply to , and prevents improper manipulation of . This knowledge requires that the compiler determine the type of and how that type interacts with the contexts in which appears.

-

To generate code that manipulates 's value, the compiler must know where that value will reside at runtime. If has internal structure, as with an array, structure, string, or record, the compiler needs a formula to find and access individual elements inside . The compiler must determine, for each value that the program will compute, where that value will reside.

To complicate matters, executable programs typically include code compiled at different times. The compiler writer must design mechanisms that allow the results of the separate compilations to interoperate correctly and seamlessly. That process begins with syntax-driven translation to build an IR representation of the code. It continues with further analysis and refinement. It relies on carefully planned interactions between procedures and name spaces (see Chapter 6).

5.3 Syntax-Driven Translation

Syntax-driven translation is a collection of techniques that compiler writers use to tie compile-time actions to the grammatical structure of the input program. The front end discovers that structure as it parses the code. The compiler writer provides computations that the parser triggers at specific points in the parse. In an LR(1) parser, those actions are triggered when the parser performs a reduction.

5.3.1 A First Example

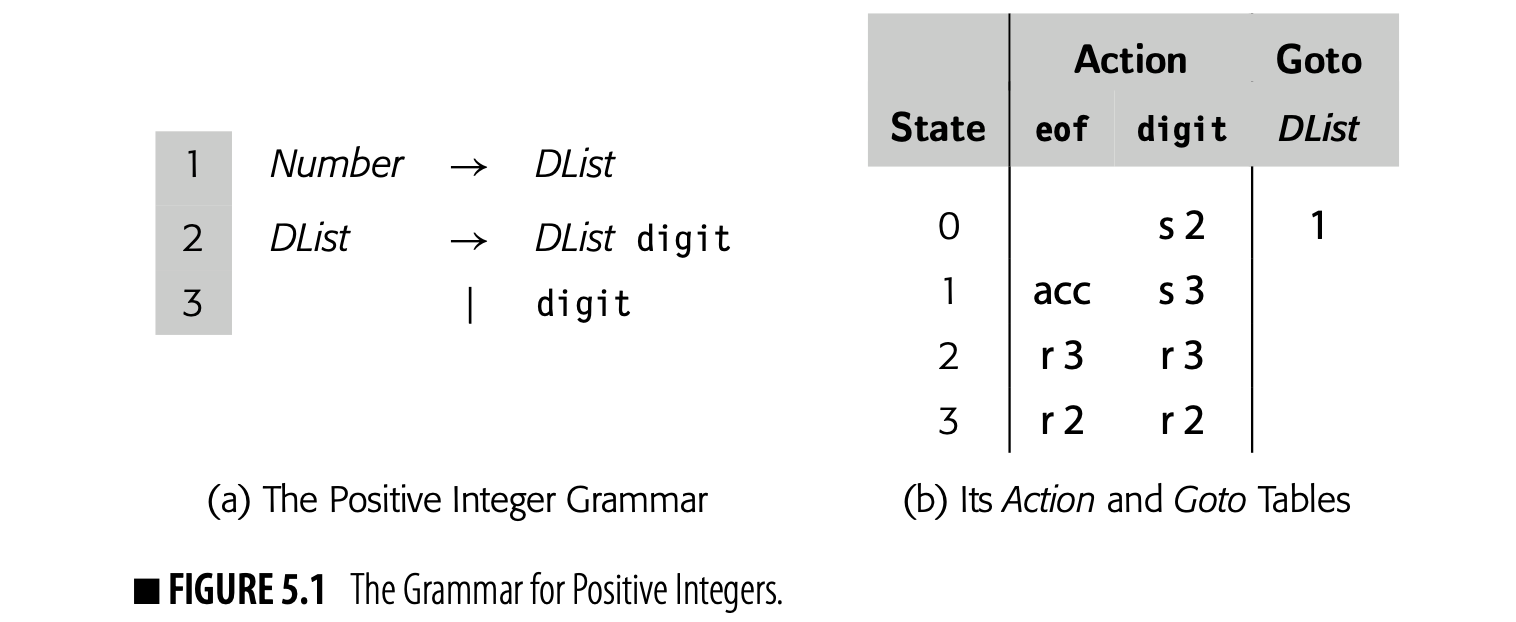

Fig. 5.1(a) shows a simple grammar that describes the set of positive integers. We can use syntax-driven actions tied to this grammar to compute the value of any valid positive integer.

Panel (b) contains the Action and Goto tables for the grammar. The parser has three possible reductions, one per production.

- The parser reduces by rule 3, , on the leftmost digit in the number.

- The parser reduces by rule 2, , for each digit after the first digit.

- The parser reduces by rule 1, after it has already reduced the last digit.

The parser can compute the integer's value with a series of production-specific tasks. It can accumulate the value left to right and, with each new digit, multiply the accumulated value by ten and add the next digit. Values are associated with each symbol used in the parse. We can encode this strategy into production-specific rules that are applied when the parser reduces.

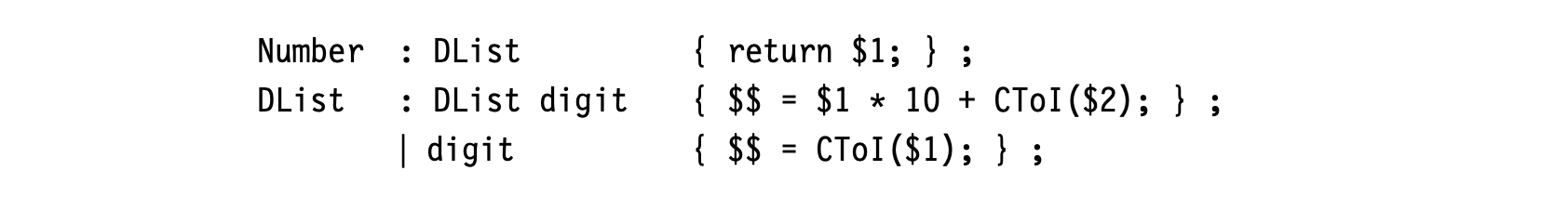

Using the notation popularized by the parser generators yacc and bison, the rules might be:

The symbols $$ ,$1 and $2 refer to values associated with grammar symbols in the production. $$ refers to the nonterminal symbol on the rule's left-hand side (LHS). The symbol i refers to the value for the _i_th symbol on the rule's right-hand side (RHS).

The symbols $$ ,$1 and $2 refer to values associated with grammar symbols in the production. $$ refers to the nonterminal symbol on the rule's left-hand side (LHS). The symbol i refers to the value for the _i_th symbol on the rule's right-hand side (RHS).

The example assumes that CTo1() converts the character from the lexeme to an integer. The compiler writer must pay attention to the types of the stack cells represented by $$, $1, and so on.

Recall that the initial on the stack repre- sents the pair ⟨INVALID, INVALID⟩.

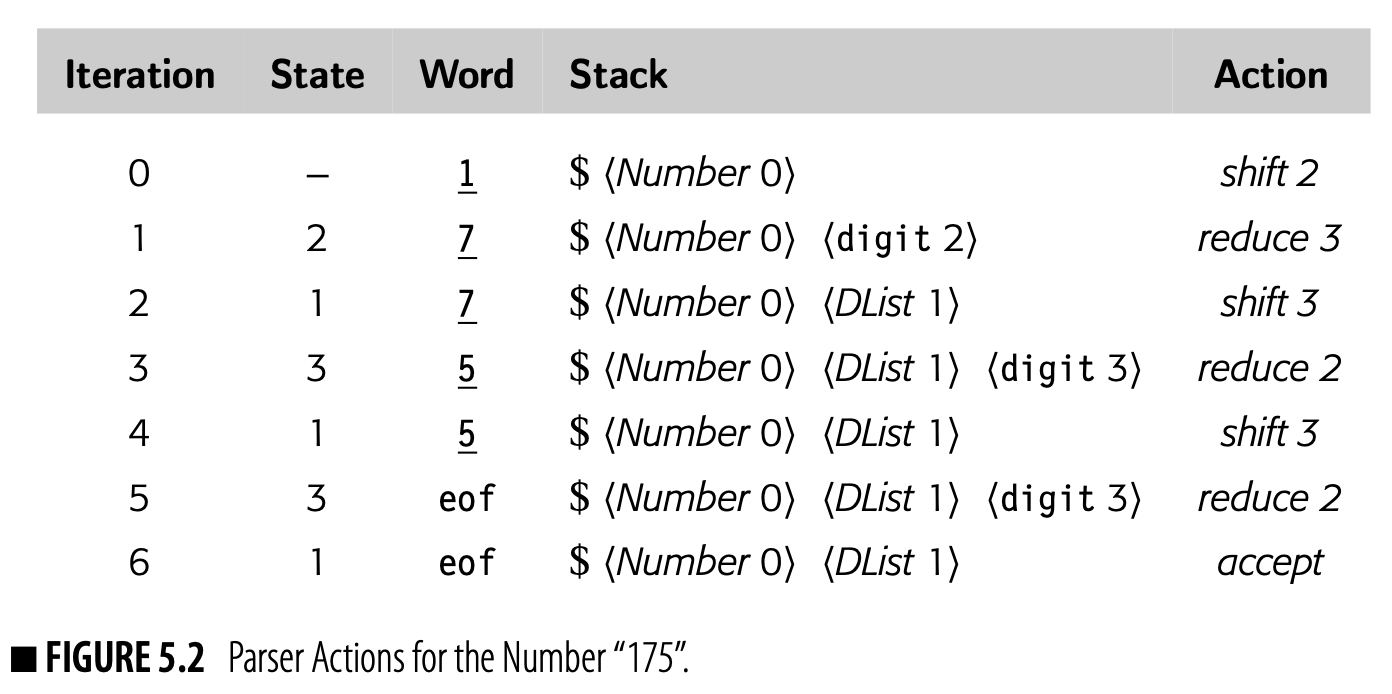

Using the Action and Goto tables from Fig. 5.1(b) to parse the string "175", an LR(1) parser would take the sequence of actions shown in Fig. 5.2. The reductions, in order, are: reduce 3, reduce 2, reduce 2, and accept.

- Reduce 3 applies rule 3's action with the integer 1 as the value of digit. The rule assigns one to the LHS_DList_.

- Reduce 2 applies rule 2's action, with 1 as the RHS_DList_'s value and the integer 7 as the digit. It assigns + = to the LHS_DList_.

- Reduce 2 applies rule 2's action, with 17 as the RHS_DList_'s value and 5 as the digit. It assigns + = to the LHS_DList_.

- The accept action, which is also a reduction by rule 1, returns the value of the LHS_DList_, which is 175.

The reduction rules, applied in the order of actions taken by the parser, create a simple framework that computes the integer's value.

The critical observation is that the parser applies these rules in a predictable order, driven by the structure of the grammar and the parse of the input string. The compiler writer specifies an action for each reduction; the sequencing and application of those actions depend entirely on the grammar and the input string. This kind of syntax-driven computation forms a programming paradigm that plays a central role in translation and finds many other applications.

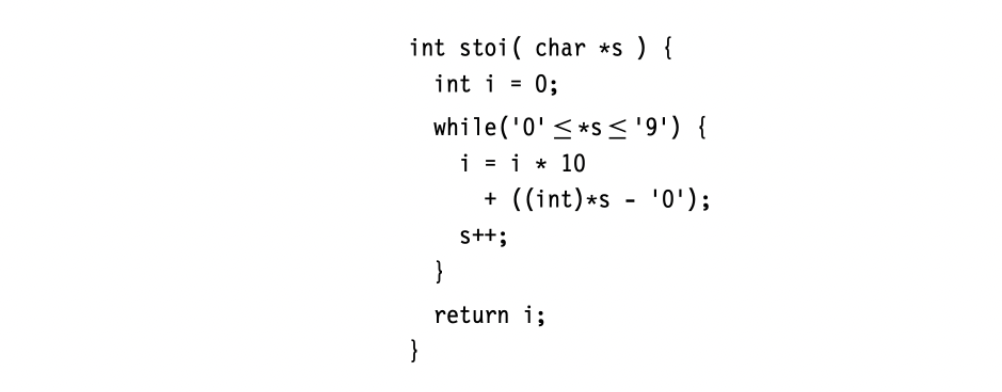

Of course, this example is overkill. A real system would almost certainly perform this same computation in a small, specialized piece of code, similar to the one in the margin. It implements the same computation, without the overhead of the more general scanning and parsing algorithms. In practice, this code would appear inline rather than as a function call. (The call overhead likely exceeds the cost of the loop.) Nonetheless, the example works well for explaining the principles of syntax-driven computation.

Of course, this example is overkill. A real system would almost certainly perform this same computation in a small, specialized piece of code, similar to the one in the margin. It implements the same computation, without the overhead of the more general scanning and parsing algorithms. In practice, this code would appear inline rather than as a function call. (The call overhead likely exceeds the cost of the loop.) Nonetheless, the example works well for explaining the principles of syntax-driven computation.

An Equivalent Treewalk Formulation

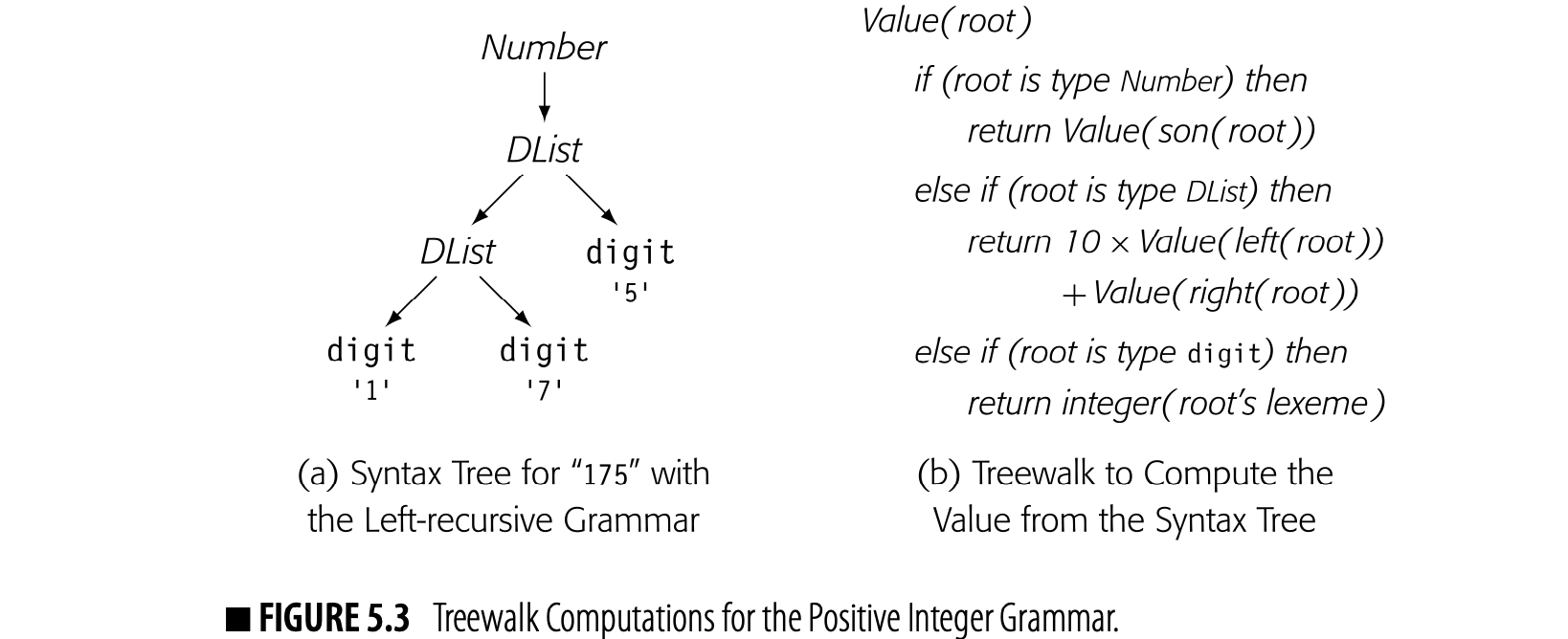

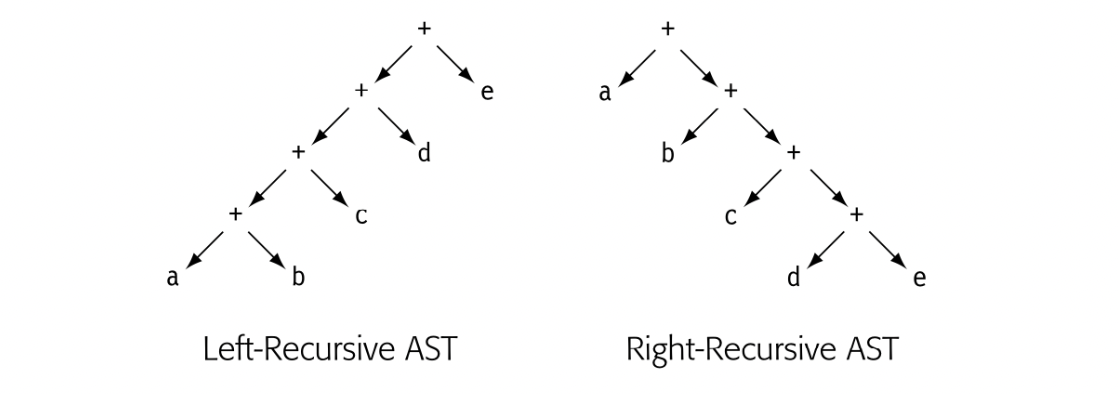

These integer-grammar value computations can also be written as recursive treewalks over syntax trees. Fig. 5.3(a) shows the syntax tree for "175" with the left recursive grammar. Panel (b) shows a simple treewalk to compute its value. It uses "integer(c)" to convert a single character to an integer value.

The treewalk formulation exposes several important aspects of yacc-style syntax-driven computation. Information flows up the syntax tree from the leaves toward the root. The action associated with a production only has names for values associated with grammar symbols named in the production. Bottom-up information flow works well in this paradigm. Top-down information flow does not.

The restriction to bottom-up information flow might appear problematic. In fact, the compiler writer can reach around the paradigm and evade these restrictions by using nonlocal variables and data structures in the "actions." Indeed, one use for a compiler's symbol table is precisely to provide nonlocal access to data derived by syntax-driven computations.

In principle, any top-down information flow problem can be solved with a bottom-up framework by passing all of the information upward in the tree to a common ancestor and solving the problem at that point. In practice, that idea does not work well because (1) the implementor must plan all the information flow; (2) she must write code to implement it; and (3) the computed result appears at a point in the tree far from where it is needed. In practice, it is often better to rethink the computation than to pass all of that information around the tree.

Form of the Grammar

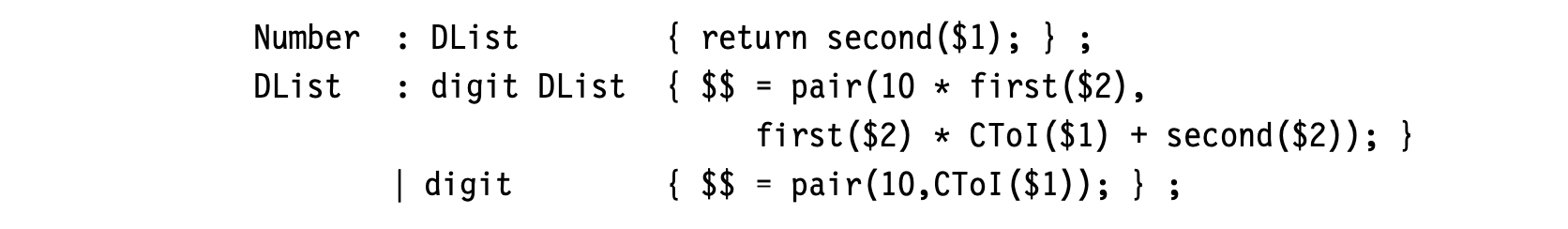

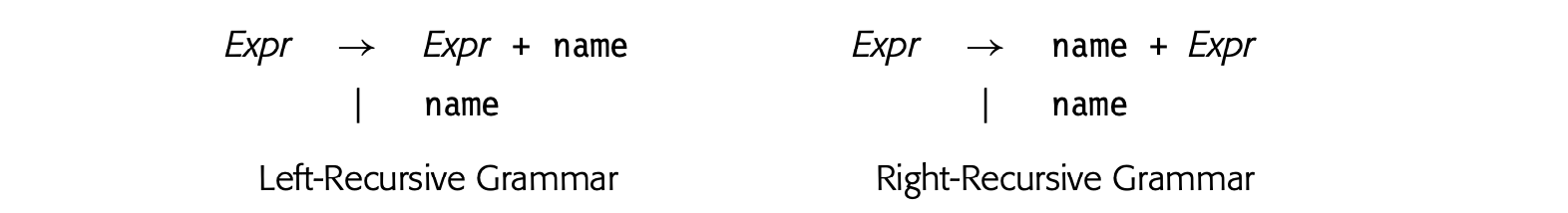

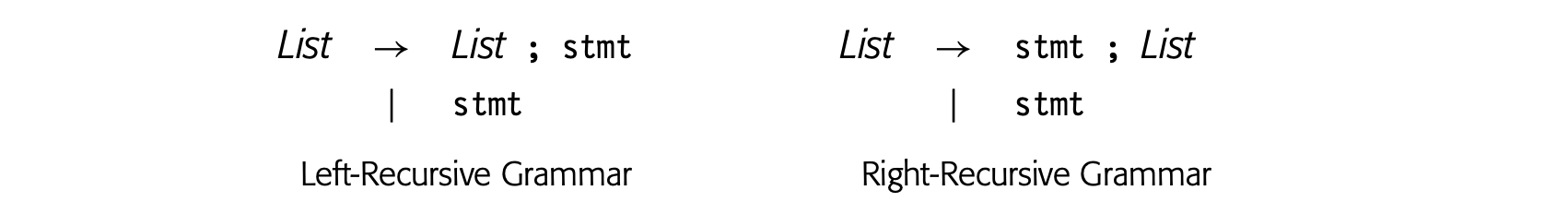

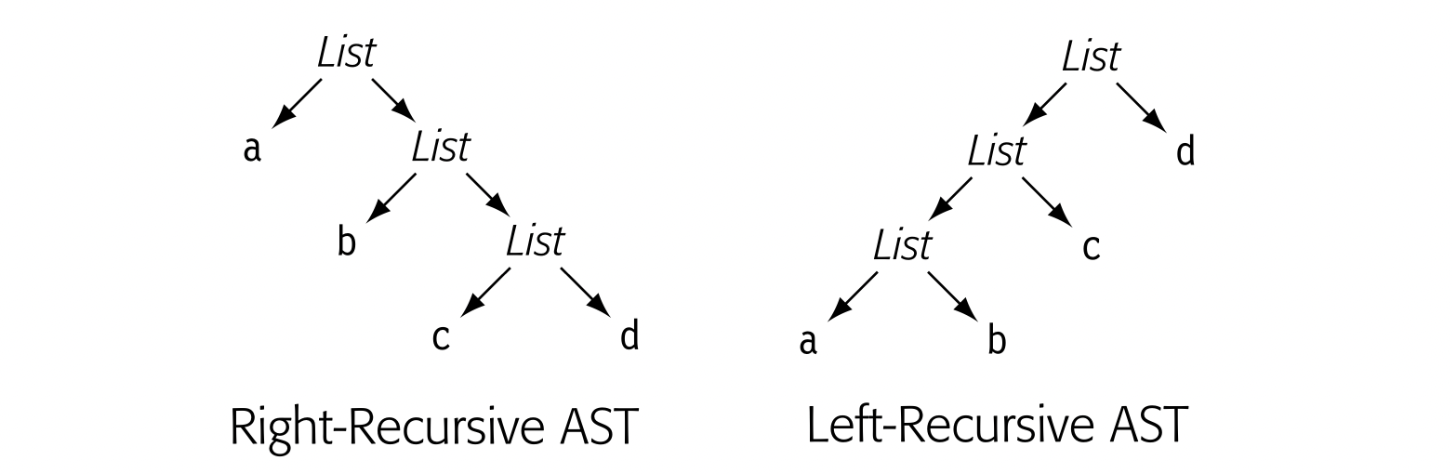

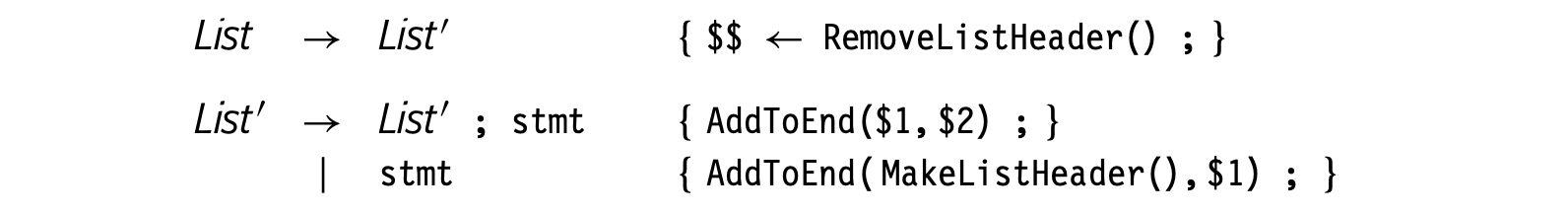

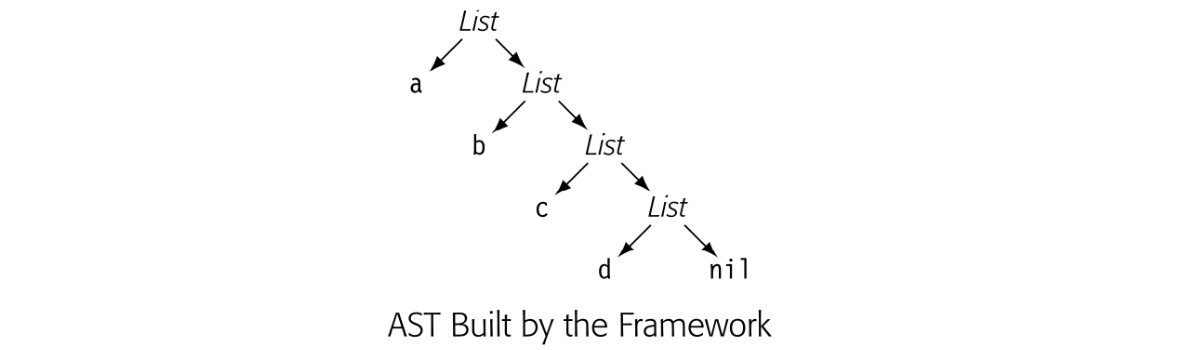

Because the grammar dictates the sequence of actions, its shape affects the computational strategy. Consider a right-recursive version of the grammar for positive integers. It reduces the rightmost digit first, which suggests the following approach:

This scheme accumulates, right to left, both a multiplier and a value. To store both values with a DList, it uses a pair constructor and the functions first and second to access a pair's component values. While this paradigm works, it is much harder to understand than the mechanism for the left-recursive grammar.

In grammar design, the compiler writer should consider the kinds of computation that she wants the parser to perform. Sometimes, changing the grammar can produce a simpler, faster computation.

5.3.2 Translating Expressions

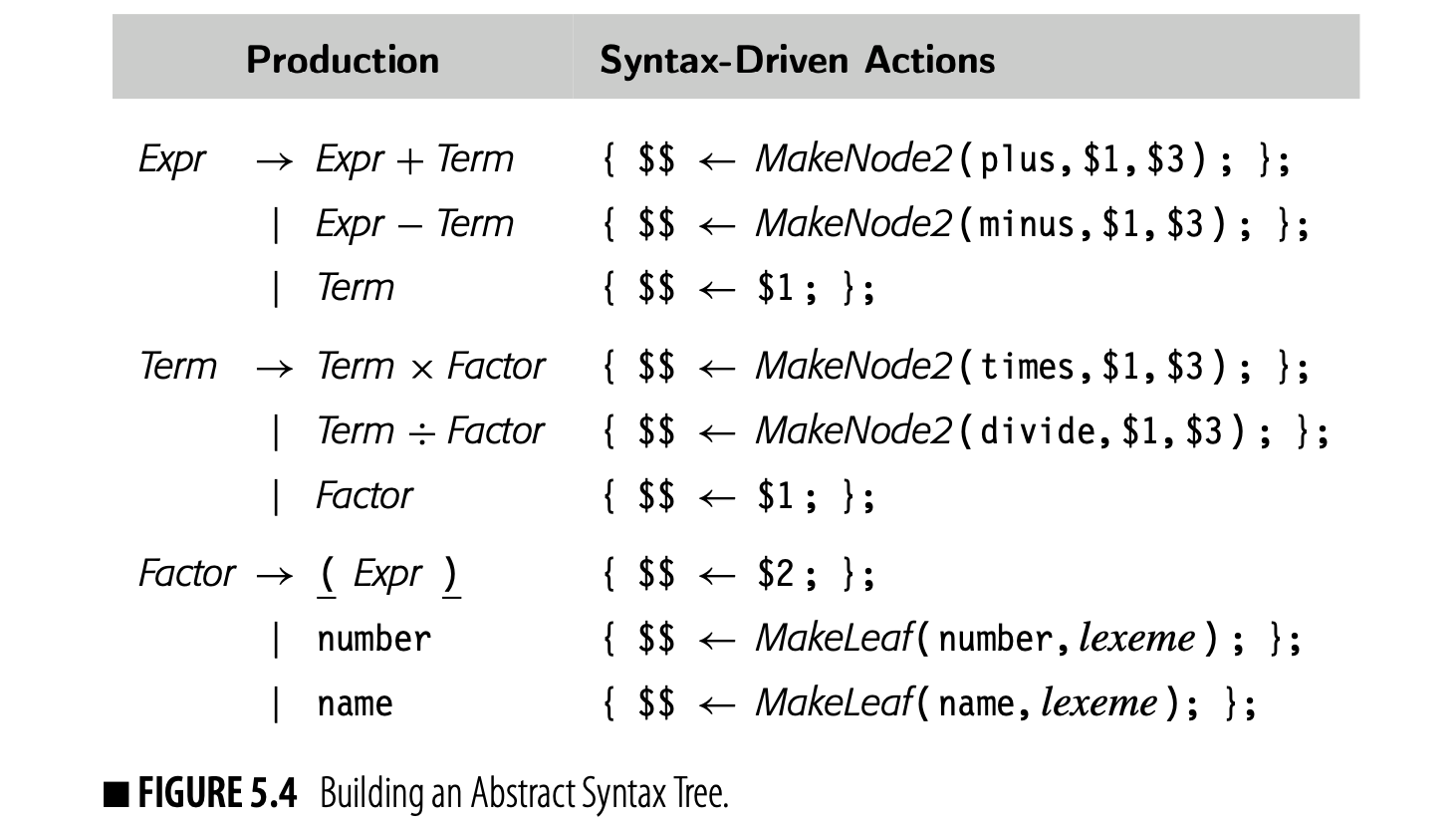

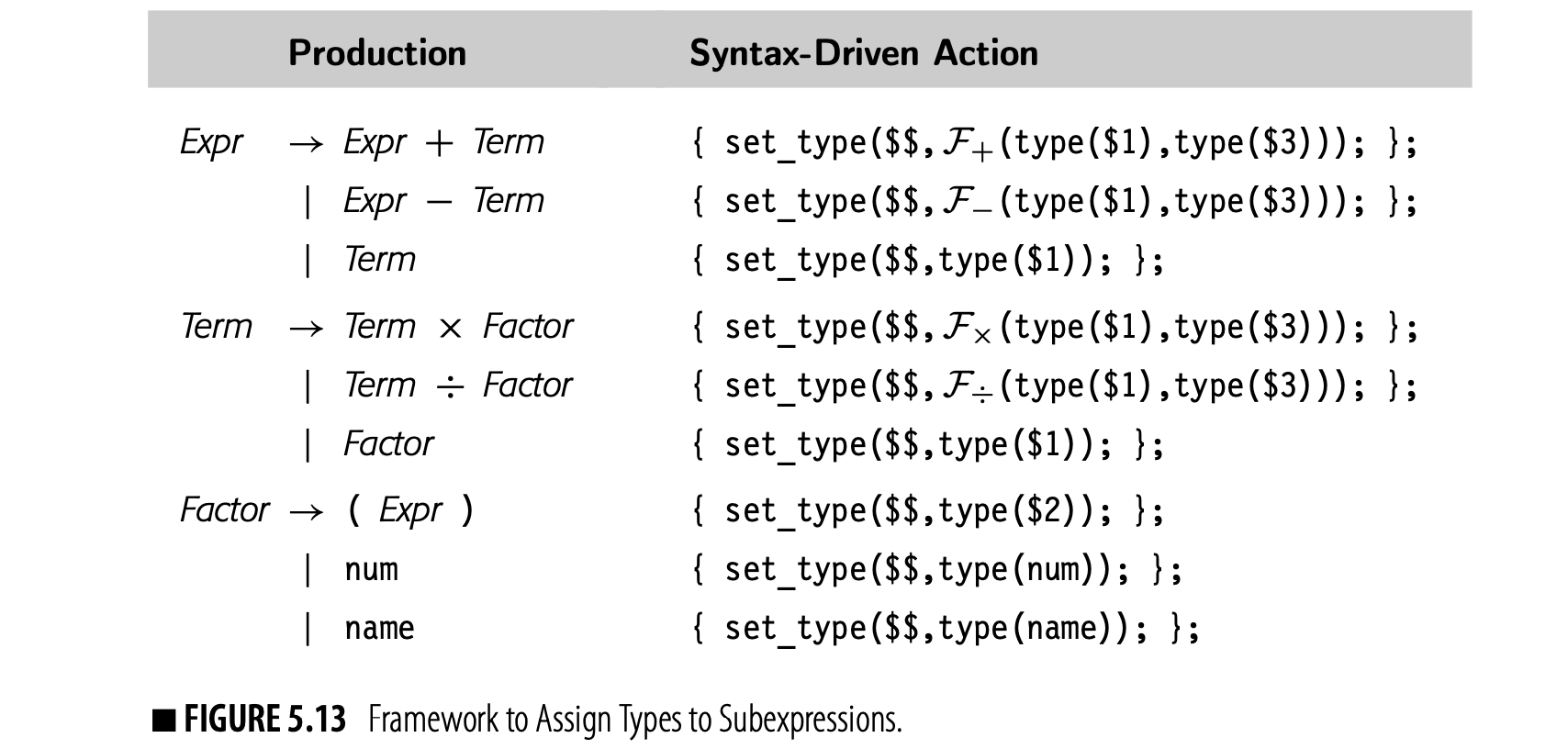

Expressions form a large portion of most programs. If we consider them as trees--that is, trees rather than directed acyclic graphs--then they are a natural example for syntax-driven translation. Fig. 5.4 shows a simple syntax-driven framework to build an abstract syntax tree for expressions. The rules are simple.

- If a production contains an operator, it builds an interior node to represent the operator.

- If a production derives a name or number, it builds a leaf node and records the lexeme.

- If the production exists to enforce precedence, it passes the AST for the subexpression upward.

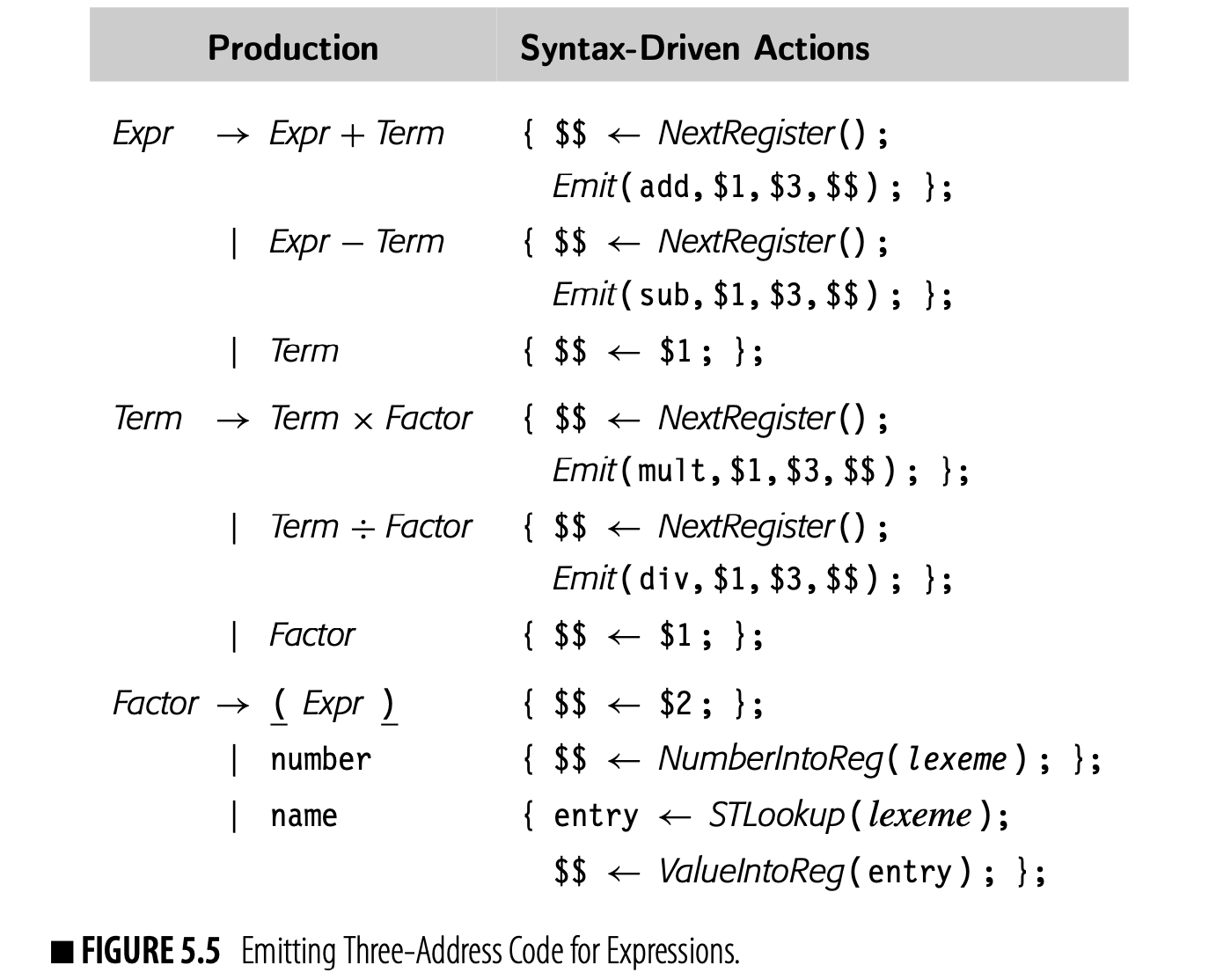

The code uses two constructors to build the nodes. builds a binary node of type with children and . builds a leaf node and associates it with the lexeme . For the expression , this translation scheme would build the simple AST shown in the margin. ASTs have a direct and obvious relationship to the grammatical structure of the input program. Three-address code lacks that direct mapping. Nonetheless, a syntax-driven framework can easily emit three-address code for expressions and assignments. Fig. 5.5 shows a syntax-driven framework to emit -like code from the classic expression grammar. The framework assumes that values reside in memory at the start of the expression.

To simplify the framework, the compiler writer has provided high-level functions to abstract away the details of where values are stored.

- NextRegister returns a new register number.

- NumberInfoReg returns the number of a register that holds the constant value from the lexeme.

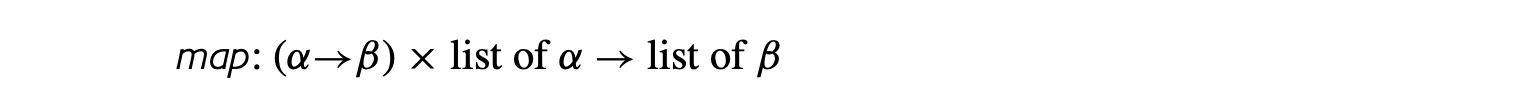

- STLookup takes a name as input and returns the symbol table entry for the entity to which the name is currently bound.

- ValueIntoReg returns the number of a register that holds the current value of the name from the lexeme.

If the grammar included assignment, it would need a helper function RegIn- toMemory to move a value from a register into memory.

Helper functions such NumberIntoReg and ValueIntoReg must emit three- address code that represents the access methods for the named entities. If the IR only has low-level operations, as occurs in ILOC, these functions can become complex. The alternative approach is to introduce high-level oper- ations into the three-address code that preserve the essential information, and to defer elaboration of these operations until after the compiler fully understands the storage map and the access methods.

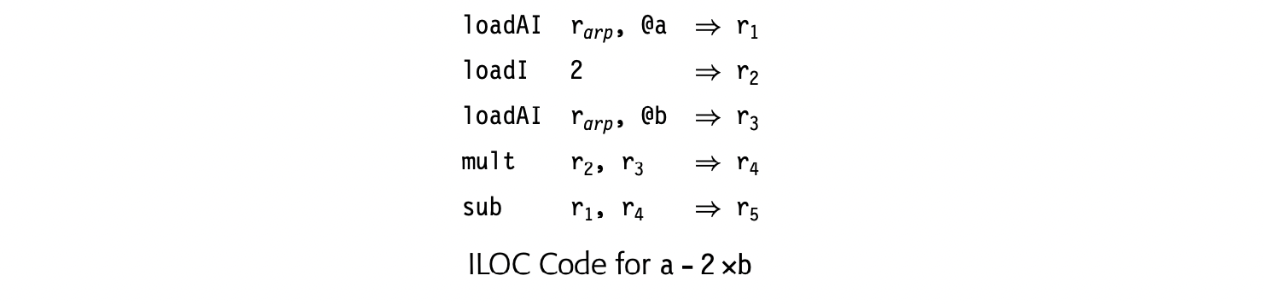

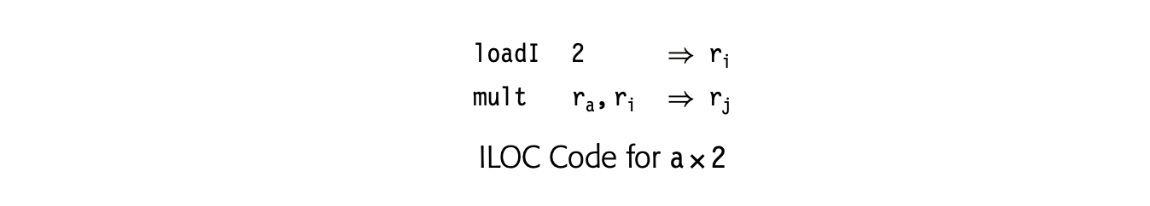

Applying this syntax-driven translation scheme to the expression produces the ILOC code shown in the margin. The code assumes that holds a pointer to the procedure's local data area and that and are the offsets from at which the program stores the values of a and b. The code leaves the result in .

Applying this syntax-driven translation scheme to the expression produces the ILOC code shown in the margin. The code assumes that holds a pointer to the procedure's local data area and that and are the offsets from at which the program stores the values of a and b. The code leaves the result in .

Implementation in an LR(1) Parser

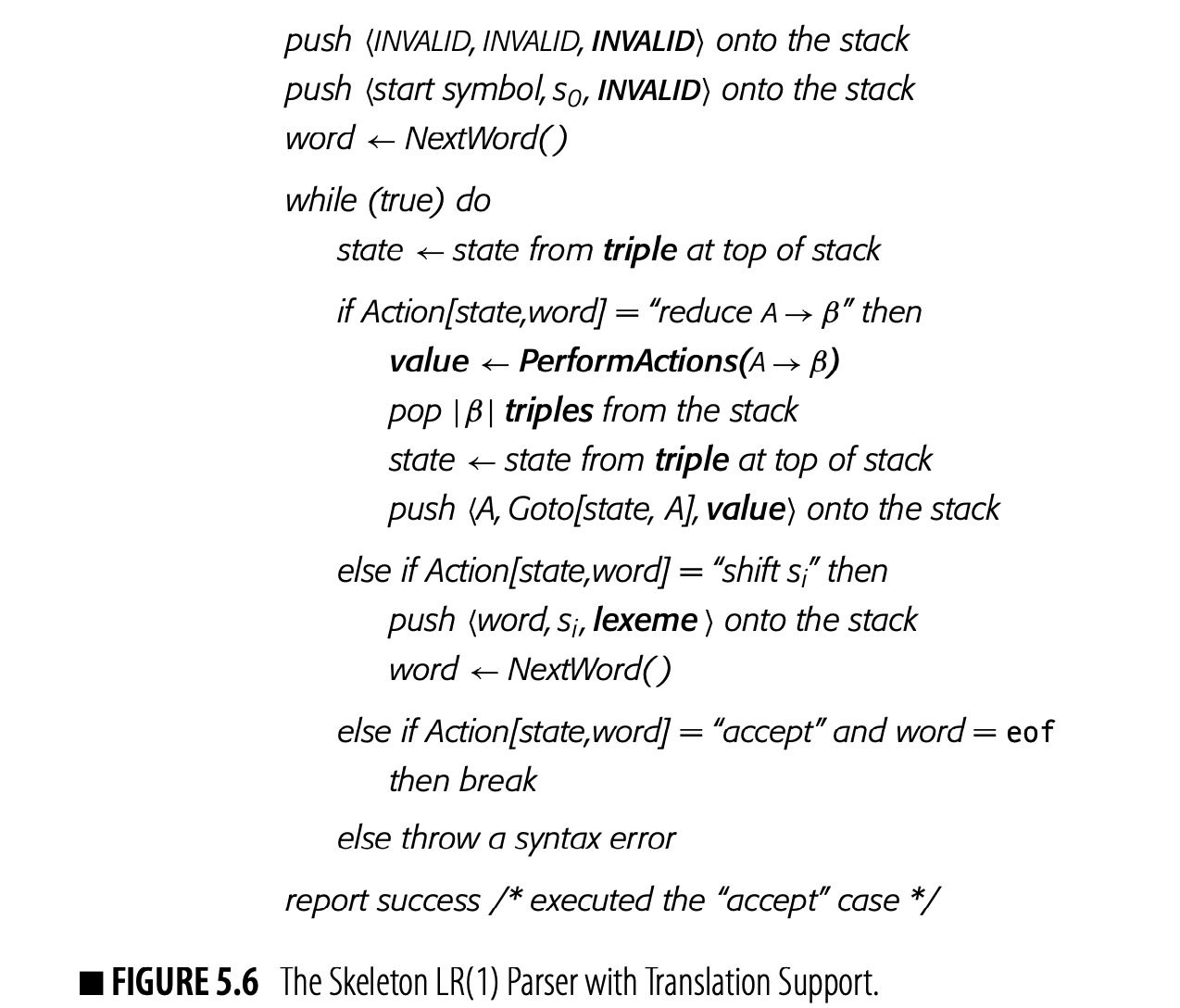

This style of syntax-driven computation was introduced in yacc, an early LALR(1) parser generator. The implementation requires two changes to the LR(1) skeleton parser. Understanding those changes sheds insight on both the yacc notation and how to use it effectively. Fig. 5.6 shows the modified skeleton LR(1) parser. Changes are typeset in bold typeface.

Parser generators differ in what value they assign to a terminal symbol.

The first change creates storage for the value associated with a grammar symbol in the derivation. The original skeleton parser stored its state in pairs kept on a stack, where symbol was a grammar symbol and state was a parser state. The modified parser replaces those pairs with triples, where value holds the entity assigned to in the reduction that shifted the triple onto the stack. Shift actions use the value of the lexeme.

The second change causes the parser to invoke a function called PerformActions before it reduces. The parser uses the result of that call in the value field when it pushes the new triple onto the stack.

The parser generator constructs PerformActions from the translation actions specified for each production in the grammar. The skeleton parser passes the function a production number; the function consists of a case statement that switches on that production number to the appropriate snippet of code for the reduction.

The remaining detail is to translate the yacc-notation symbols , and so on into concrete references into the stack. represents the return value for PerformActions. Any other symbol, , is a reference to the value field of the triple corresponding to symbol i in the production's RHS. Since those triples appear, in right to left order, on the top of the stack, translates to the value field for the triple located slots from the top of the stack.

Handling Nonlocal Computation

The examples so far only show local computation in the grammar. Individual rules can only name symbols in the same production. Many of the tasks in a compiler require information from other parts of the computation; in a treewalk formulation, they need data from distant parts of the syntax tree.

Defining occurrence The first occurrence of a name in a given scope is its defining occurrence. Any subsequent use is a reference occurrence.

One example of nonlocal computation in a compiler is the association of type, lifetime, and visibility information with a named entity, such as a variable, procedure, object, or structure layout. The compiler becomes aware of the entity when it encounters the name for the first time in a scopethe name's defining occurrence. At the defining occurrence of a name x, the compiler must determine x's properties. At subsequent reference occurrences, the compiler needs access to those previously determined properties.

The use of a global symbol table to provide nonlocal access is analogous to the use of global variables in imperative programs.

The kinds of rules introduced in the previous example provide a natural mechanism to pass information up the parse tree and to perform local computation-between values associated with a node and its children. To translate an expression such as x+y into a low-level three-address IR, the compiler must access information that is distant in the parse tree--the declarations of x and y. If the compiler tries to generate low-level three-address code for the expression, it may also need access to information derived from the syntax, such as a determination as to whether or not the code can keep x in a register--that is, whether or not x is ambiguous. A common way to address this problem is to store information needed for nonlocal computations in a globally accessible data structure. Most compilers use a symbol table for this purpose (see Section 4.5).

The "symbol table" is actually a complex set of tables and search paths. Conceptually, the reader can think of it as a hashmap tailored to each scope. In a specific scope, the search path consists of an ordered list of tables that the compiler will search to resolve a name.

In a dynamically typed language such as PYTHON, statements that define x may change attributes

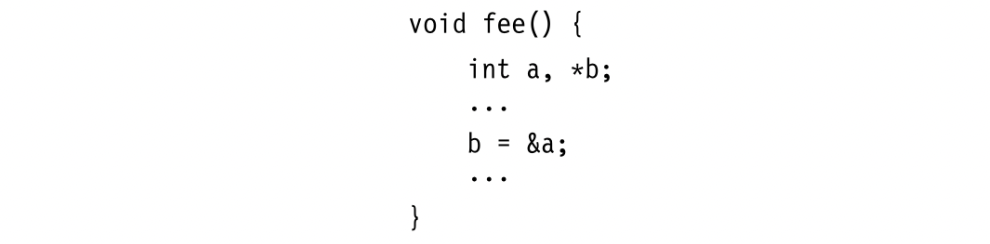

Different parts of the grammar will manipulate the symbol table representation. A name's defining occurrence creates its symbol table entry. Its declarations, if present, set various attributes and bindings. Each reference occurrence will query the table to determine the name's attributes. Statements that open a new scope, such as a procedure, a block, or a structure declaration, will create new scopes and link them into the search path. More subtle issues may arise; if a C program takes the address of a variable a, as in 8a, the compiler should mark a as potentially ambiguous.

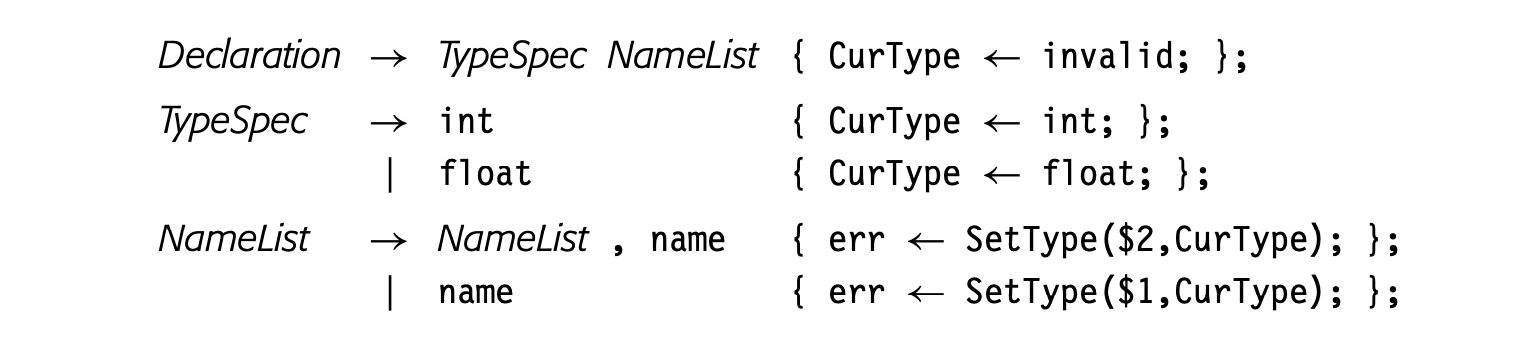

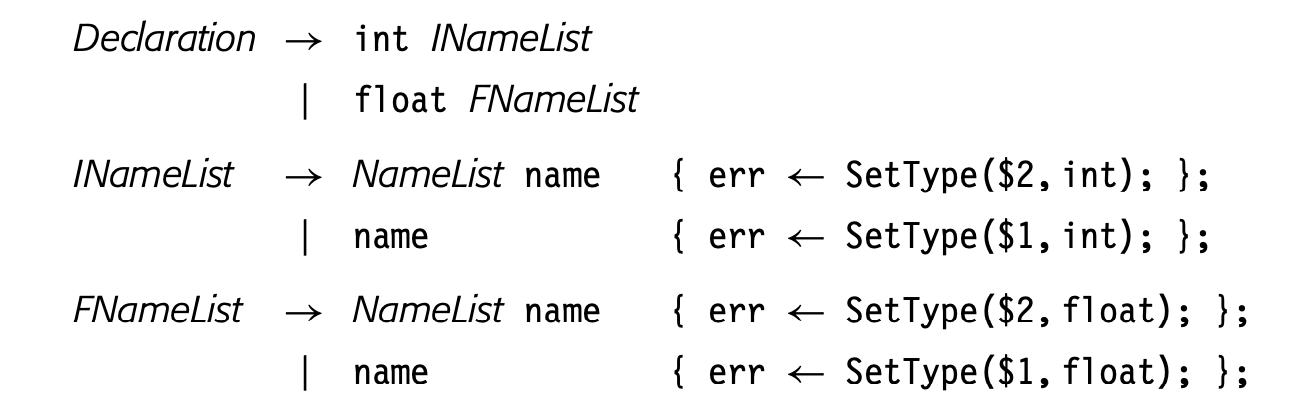

The same trick, using a global variable to communicate information between the translation rules, arises in other contexts. Consider a source language with a simple declaration syntax. The parser can create symbol-table entries for each name and record their attributes as it processes the declarations. For example, the source language might include syntax similar to the following set of rules:

where

where SetType creates a new entry for name if none exists and reports an error if name exists and has a designated type other than CurType.

The type of the declared variables is determined in the productions for _TypeSpec_. The action for _TypeSpec_ records the type into a global variable, CurType. When a name appears in the _NameList_ production, the action sets the name's type to the value in _CurType_. The compiler writer has reachedaround the paradigm to pass information from the RHS of one production to the RHS of another.

SINGLE-PASS COMPILERS

In the earliest days of compilation, implementors tried to build single-pass compilers—translators that would emit assembly code or machine code in a single pass over the source program. At a time when fast computers were measured in kiloflops, the efficiency of translation was an important issue.

To simplify single-pass translation, language designers adopted rules meant to avoid the need for multiple passes. For example, PASCAL requires that all declarations occur before any executable statement; this restriction allowed the compiler to resolve names and perform storage layout before emitting any code. In hindsight, it is unclear whether these restrictions were either necessary or desirable.

Making multiple passes over the code allows the compiler to gather more information and, in many cases, to generate more efficient code, as Floyd observed in 1961 [160]. With today’s more complex processors, almost all compilers perform multiple passes over an IR form of the code.

Form of the Grammar

The form of the grammar can play an important role in shaping the computation. To avoid the global variable CurType in the preceding example, the compiler writer might reformulate the grammar for declaration syntax as follows:

This form of the grammar accepts the same language. However, it creates distinct name lists for int and float names, As shown, the compiler writer can use these distinct productions to encode the type directly into the syntax-directed action. This strategy simplifies the translation framework and eliminates the use of a global variable to pass information between the productions. The framework is easier to write, easier to understand, and, likely, easier to maintain. Sometimes, shaping the grammar to the computation can simplify the syntax-driven actions.

Tailoring Expressions to Context

A more subtle form of nonlocal computation can arise when the compiler writer needs to make a decision based on information in multiple productions. For example, consider the problem of extending the framework in Fig. 5.5 so that it can emit an immediate multiply operation (mult1 in ILOC) when translating an expression. In a single-pass compiler, for example, it might be important to emit the mult1 in the initial IR.

For the expression , the framework in Fig. 5.5 would produce something similar to the code shown in the margin. (The code assumes that a resides in .) The reduction by emits the load1; it executes before the reduction by .

For the expression , the framework in Fig. 5.5 would produce something similar to the code shown in the margin. (The code assumes that a resides in .) The reduction by emits the load1; it executes before the reduction by .

To recognize the opportunity for a mult1, the compiler writer would need to add code to the action for that recognizes when 1. Even with this effort, the load1 would remain. Subsequent optimization could remove it (see Section 10.2).

The fundamental problem is that the actions in our syntax-driven translation can only access local information because they can only name symbols in the current production. That structure forces the translation to emit the load1 before it can know that the value's use occurs in an operation that has an "immediate" variant.

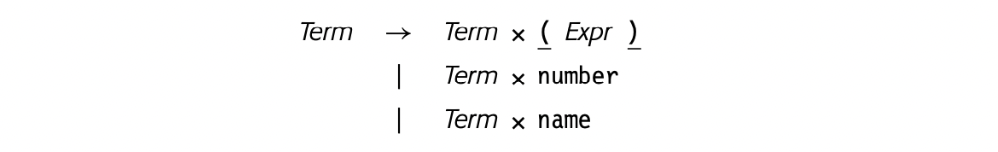

The obvious suggestion is to refactor the grammar to reflect the mult1 case. If the compiler writer rewrites with the three productions shown in the margin, then she can emit a mult1 in the action for , which will catch the case a x2. It will not, however, catch the case 2 x a. Forward substitution on the left operand will not work, because the grammar is left recursive. At best, forward substitution can expose either an immediate left operand or an immediate right operand.

The obvious suggestion is to refactor the grammar to reflect the mult1 case. If the compiler writer rewrites with the three productions shown in the margin, then she can emit a mult1 in the action for , which will catch the case a x2. It will not, however, catch the case 2 x a. Forward substitution on the left operand will not work, because the grammar is left recursive. At best, forward substitution can expose either an immediate left operand or an immediate right operand.

The most comprehensive solution to this problem is to create the more general multiply operation and allow either subsequent optimization or instruction selection to discover the opportunity and rewrite the code. Either of the techniques for instruction selection described in Chapter 11 can discover the opportunity for mult1 and rewrite the code accordingly.

Peephole optimization an optimization that applies pattern match- ing to simplify code in a small buffer

If the compiler must generate the mult1 early, the most rational approach is to have the compiler maintain a small buffer of three to four operations and to perform peephole optimization as it emits the initial IR (see Section 11.3.1). It can easily detect and rewrite inefficiencies such as this one.

5.3.3 Translating Control-Flow Statements

As we have seen, the IR for expressions follows closely from the syntax for expressions, which leads to straightforward translation schemes. Control-flow statements, such as nested if-then-else constructs or loops, can require more complex representations.

Building an AST

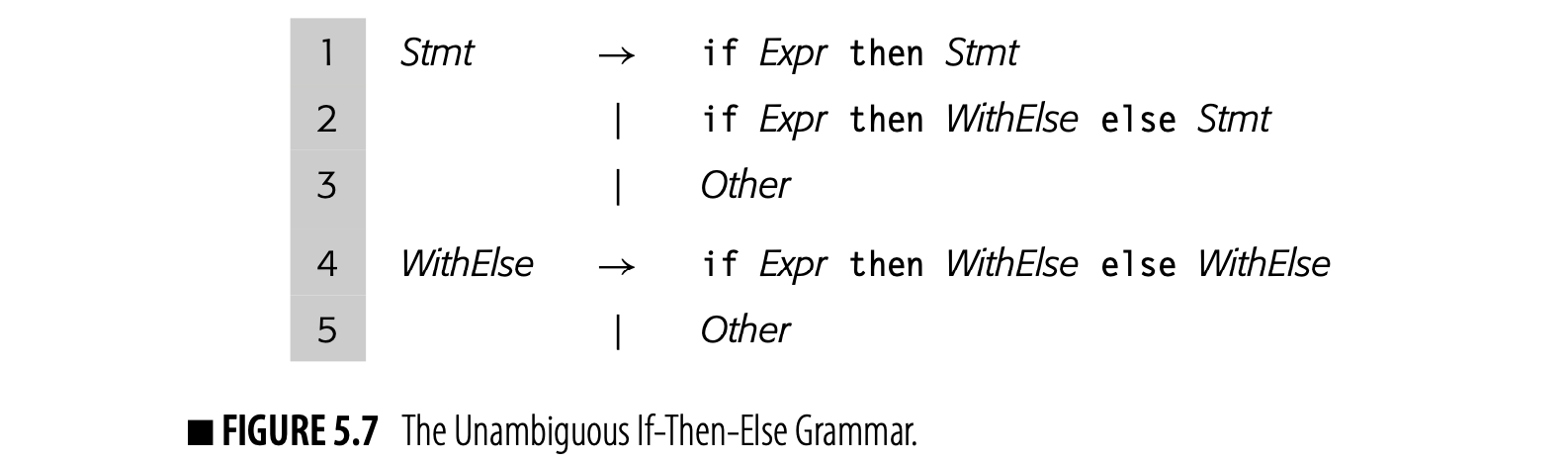

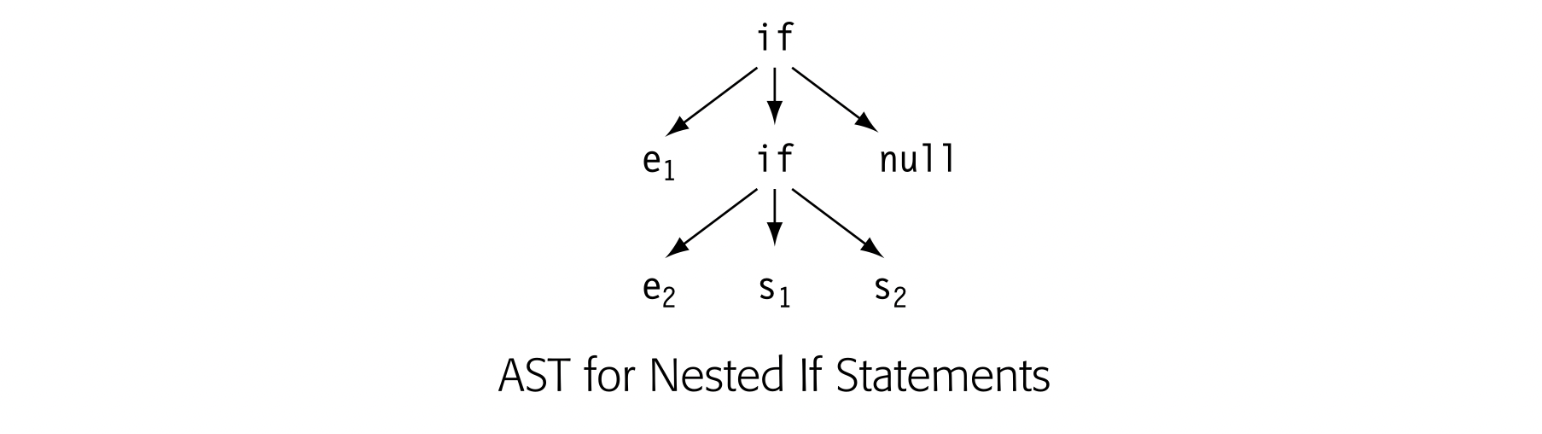

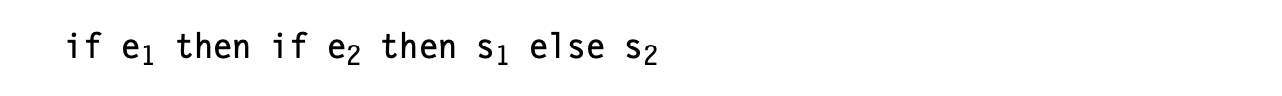

The parser can build an AST to represent control-flow constructs in a natural way. Consider a nest of if-then-else constructs, using the grammar from Fig. 5.7. The AST can use a node with three children to represent the if. One child holds the control expression; another holds the statements in the then clause; the third holds the statements in the else clause. The drawing in the margin shows the AST for the input:

The parser can build an AST to represent control-flow constructs in a natural way. Consider a nest of if-then-else constructs, using the grammar from Fig. 5.7. The AST can use a node with three children to represent the if. One child holds the control expression; another holds the statements in the then clause; the third holds the statements in the else clause. The drawing in the margin shows the AST for the input:

The actions to build this AST are straightforward.

The actions to build this AST are straightforward.

Building Three-Address Code

To translate an if-then-else construct into three-address code, the compiler must encode the transfers of control into a set of labels, branches, and jumps. The three-address IR resembles the obvious assembly code for the construct:

- evaluate the control expression;

- branch to the then subpart (s1) or the else subpart (s2) as appropriate;

- at the end of the selected subpart, jump to the start of the statement that follows the

if-then-elseconstruct-the "exit."

This translation scheme requires labels for the then part, the else part, and the exit, along with a branch and two jumps.

Production 4 in the grammar from Fig. 5.7 shows the issues that arise in a translation scheme to emit ILOC-like code for an if-then-else. Other productions will generate the IR to evaluate the Expr and to implement the then and else parts. The scheme for rule 4 must combine these disjoint parts into code for a complete if-then-else.

The complication with rule 4 lies in the fact that the parser needs to emit IR at several different points: after the Expr has been recognized, after the WithElse in the then part has been recognized, and after the WithElse in the else part has been recognized. In a straightforward rule set, the action for rule 4 would execute after all three of those subparts have been parsed and the IR for their evaluation has been created.

The complication with rule 4 lies in the fact that the parser needs to emit IR at several different points: after the Expr has been recognized, after the WithElse in the then part has been recognized, and after the WithElse in the else part has been recognized. In a straightforward rule set, the action for rule 4 would execute after all three of those subparts have been parsed and the IR for their evaluation has been created.

The scheme for rule 4 must have several different actions, triggered at different points in the rule. To accomplish this goal, the compiler writer can modify the grammar in a way that creates reductions at the points in the parse where the translation scheme needs to perform some action.

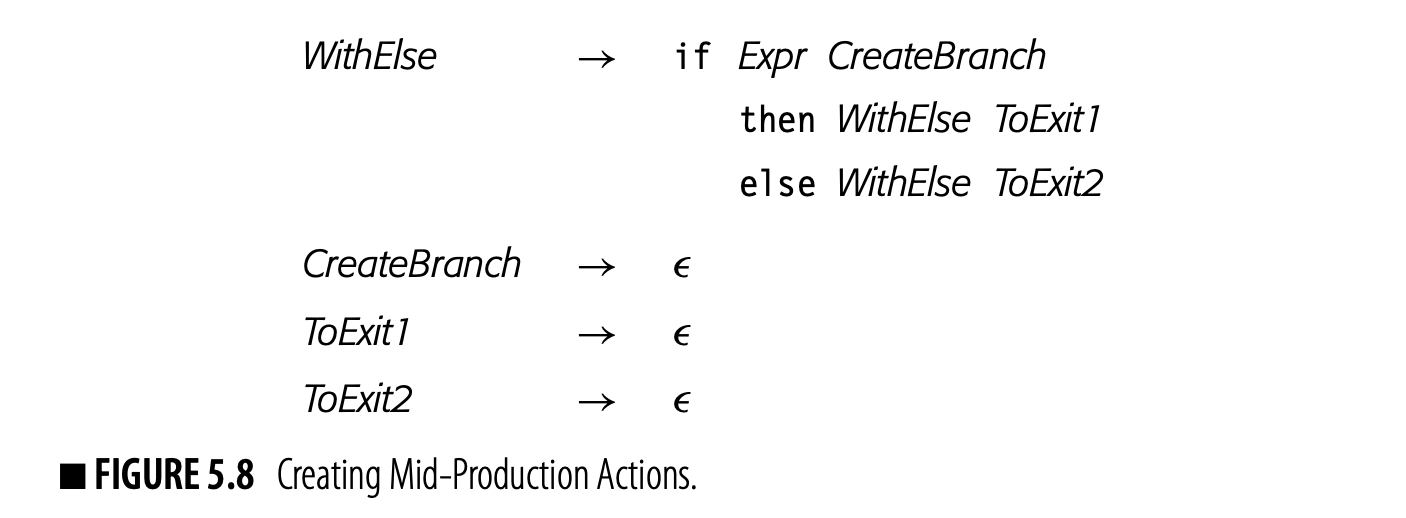

Fig. 5.8 shows a rewritten version of production 4 that creates reductions at the critical points in the parse of a nested if-then-else construct. It introduces three new nonterminal symbols, each defined by an epsilon production.

The compiler could omit the code for

ToExit2and rely on the fall-through case of the branch. Making the branch explicit rather than implicit gives later passes more freedom to reorder the code (see Section 8.6.2).

The reduction for CreateBranch can create the three labels, insert the conditional branch, and insert a nop with the label for the then part. The reduction for ToEit1 inserts a jump to the exit label followed by a nop with the label for the else part. Finally, ToEit2 inserts a jump to the exit label followed by a nop with the exit label.

One final complication arises. The compiler writer must account for nested constructs. The three labels must be stored in a way that both ties them to this specific instance of a WithElse and makes them accessible to the other actions associated with rule 4. Our notation, so far, does not provide a solution to this problem. The bison parser generator extended yacc notation to solve it, so that the compiler writer does not need to introduce an explicit stack of label-valued triples.

The bison solution is to allow an action between any two symbols on the production's RHS. It behaves as if bison inserts a new nonterminal at the point of the action, along with an -production for the new nonterminal. It then associates the action with this new -production. The compiler writer must count carefully; the presence of a mid-production action creates an extra name and increments the names of symbols to its right.

Using this scheme, the mid-production actions can access the stack slot associated with any symbol in the expanded production, including the symbol on the LHS of rule 4. In the if-then-else scenario, the action between Expr and then can store a triple of labels temporarily in the stack slot for that LHS,. The actions that follow the two WithElse clauses can then find the labels that they need in . The result is not elegant, but it creates a workaround to allow slightly nonlocal access.

Case statements and loops present similar problems. The compiler needs to encode the control-flow of the original construct into a set of labels, branches, and jumps. The parse stack provides a natural way to keep track of the information for nested control-flow structures.

Section Review

As part of translation, the compiler produces an IR form of the code. To support that initial translation, parser generators provide a facility to specify syntax-driven computations that tie computation to the underlying grammar. The parser then sequences those actions based on the actual syntax of the input program.

Syntax-driven translation creates an efficient mechanism for IR generation. It easily accommodates decisions that require either local knowledge or knowledge from earlier in the parse. It cannot make decisions based on facts that appear later in the parse. Such decisions require multiple passes over the IR to refine and improve the code.

Review Questions

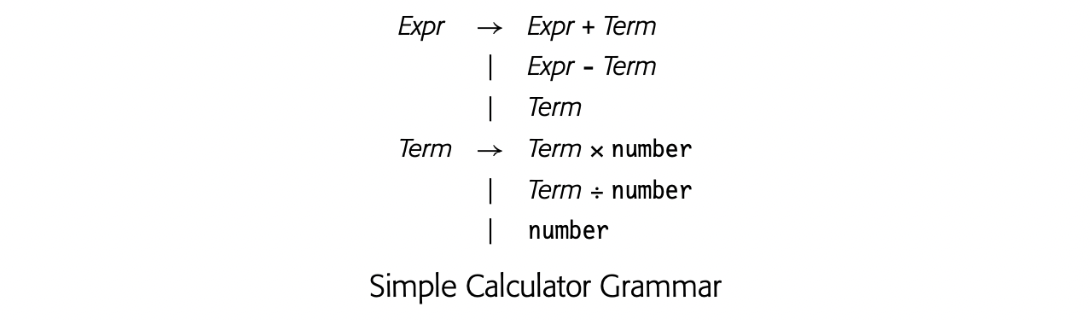

- The grammar in the margin defines the syntax of a simple four-function calculator. The calculator displays its current result on each reduction to Expr or Term. Write the actions for a syntax-driven scheme to evaluate expressions with this grammar.

- Consider the grammar from Fig. 10. Write a set of translation rules to build an AST for an if-then-else construct.

5.4 Modeling the Naming Environment

Modern programming languages allow the programmer to create complex name spaces. Most languages support some variant of a lexical naming hierarchy, where visibility, type, and lifetime are expressed in relationship to the structure of the program. Many languages also support an object-oriented naming hierarchy, where visibility and type are relative to inheritance and lifetimes are governed by explicit or implicit allocation and deallocation. During translation, optimization, and code generation, the compiler needs mechanisms to model and understand these hierarchies.

When the compiler encounters a name, its syntax-driven translation rules must map that name to a specific entity, such as a variable, object, or procedure. That name-to-entity binding plays a key role in translation, as it establishes the name's type and access method, which, in turn, govern the code that the compiler can generate. The compiler uses its model of the name space to determine this binding--a process called name resolution.

Static binding When the compiler can determine the name-to-entity binding, we consider that binding to be static, in that it does not change at runtime.

A program's name space can contain multiple subspaces, or scopes. As defined in Chapter 4, a scope is a region in the program that demarcates a name space. Inside a scope, the programmer can define new names. Names are visible inside their scope and, generally, invisible outside their scope.

Dynamic binding When the compiler cannot determine the name-to-entity binding and must defer that resolution until runtime, we consider that binding to be dynamic.

The primary mechanism used to model the naming environment is a set of tables, collectively referred to as the symbol table. The compiler builds these tables during the initial translation. For names that are bound statically, it annotates references to the name with a specific symbol table reference. For names that are bound dynamically, such as a C++ virtual function, it must make provision to resolve that binding at runtime. As the parse proceeds, the compiler creates, modifies, and discards parts of this model.

Before discussing the mechanism to build and maintain the visibility model, a brief review of scope rules is in order.

5.4.1 Lexical Hierarchies

Lexical scope Scopes that nest in the order that they are encountered in the program are often called lexical scopes.

Most programming languages provide nested lexical scopes in some form. The general principle behind lexical scope rules is simple:

At a point in a program, an occurrence of name refers to the entity named that was created, explicitly or implicitly, in the scope that is lexically closest to .

Thus, if is used in the current scope, it refers to the declared in the current scope, if one exists. If not, it refers to the declaration of that occurs in the closest enclosing scope. The outermost scope typically contains names that are visible throughout the entire program, usually called global names.

CREATING A NEW NAME Programming languages differ in the way that the programmer declares names. Some languages require a declaration for each named variable and procedure. Others determine the attributes of a name by applying rules in place at the name's defining occurrence. Still others rely on context to infer the name's attributes. The treatment of a defining occurrence of some name x in scope depends on the source language's visibility rules and the surrounding context. ■ If occurs in a declaration statement, then the attributes of in are obvious and well-defined. ■ If occurs as a reference and an instance of is visible in a scope that surrounds , most languages bind to that entity. ■ If occurs as a reference and no instance of is visible, then treatment varies by language.

APL,PYTHONand evenFORTRANcreate a new entity. treats the reference as an error.When the compiler encounters a defining occurrence, it must create the appropriate structures to record the name and its attributes and to make the name visible to name lookups.

Programming languages differ in the ways that they demarcate scopes. PASCAL marks a scope with a begin-end pair. defines a scope between each pair of curly braces, . Structure and record definitions create a scope that contains their element names. Class definitions in an OOL create a new scope for names visible in the class.

uses curly braces as the comment delimiter.

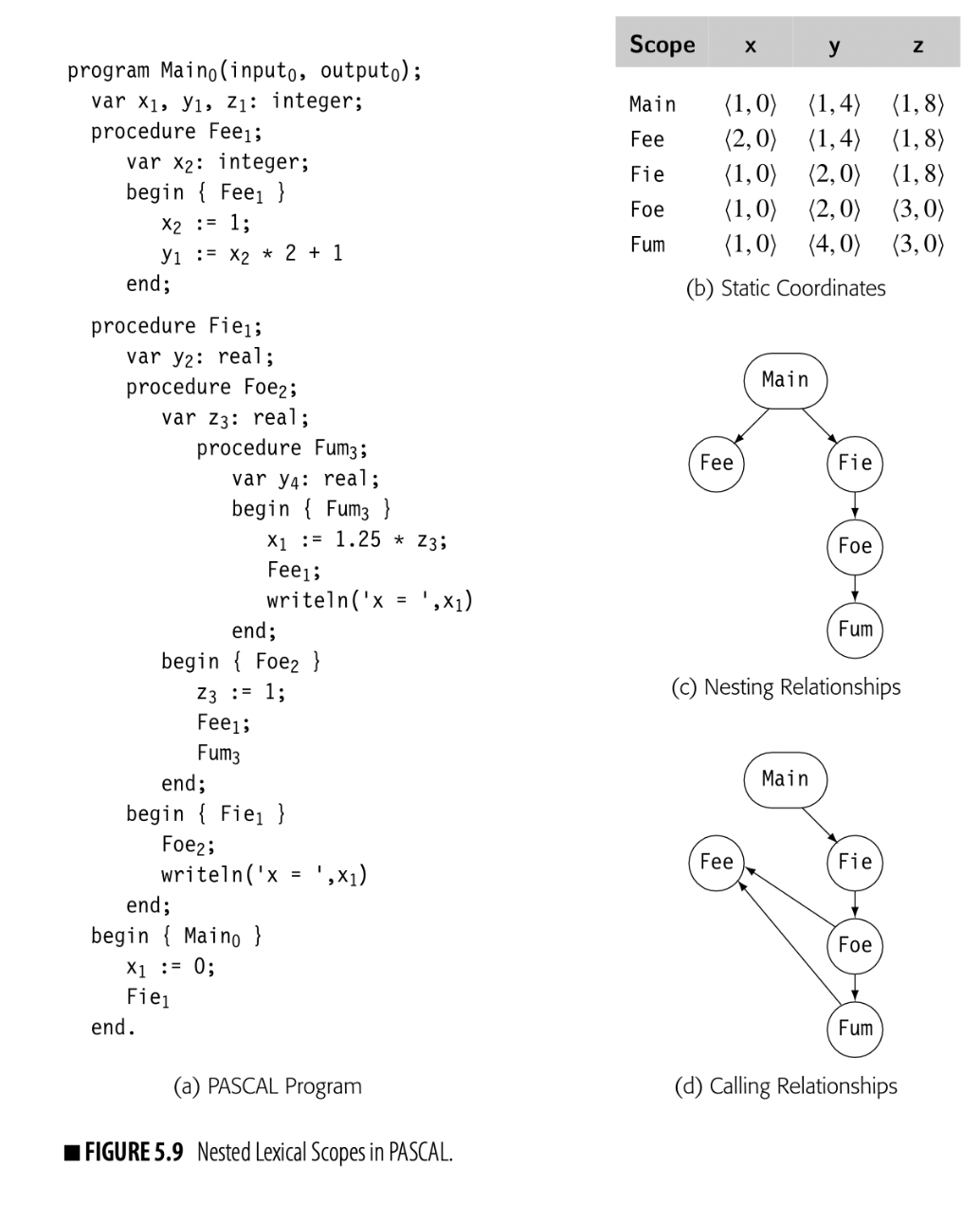

To make the discussion concrete, consider the PASCAL program shown in Fig. 5.9. It contains five distinct scopes, one for each procedure: Main, Fee, Fie, Foe, and Fum. Each procedure declares some variables drawn from the set of names x, y, and z. In the code, each name has a subscript to indicate its level number. Names declared in a procedure always have a level that is one more than the level of the procedure name. Thus, Main has level 0 , and the names x, y, z, Fee, and Fie, all declared directly in Main, have level 1 .

Static coordinate For a name x declared in scope , its static coordinate is a pair where is the lexical nesting level of and is the offset where x is stored in the scope's data area.

To represent names in a lexically scoped language, the compiler can use the static coordinate for each name. The static coordinate is a pair , where is the name's lexical nesting level and is the its offset in the data area for level . The compiler obtains the static coordinate as part of the process of name resolution--mapping the name to a specific entity.

Modeling Lexical Scopes

As the parser works its way through the input code, it must build and maintain a model of the naming environment. The model changes as the parser enters and leaves individual scopes. The compiler's symbol table instantiates that model.

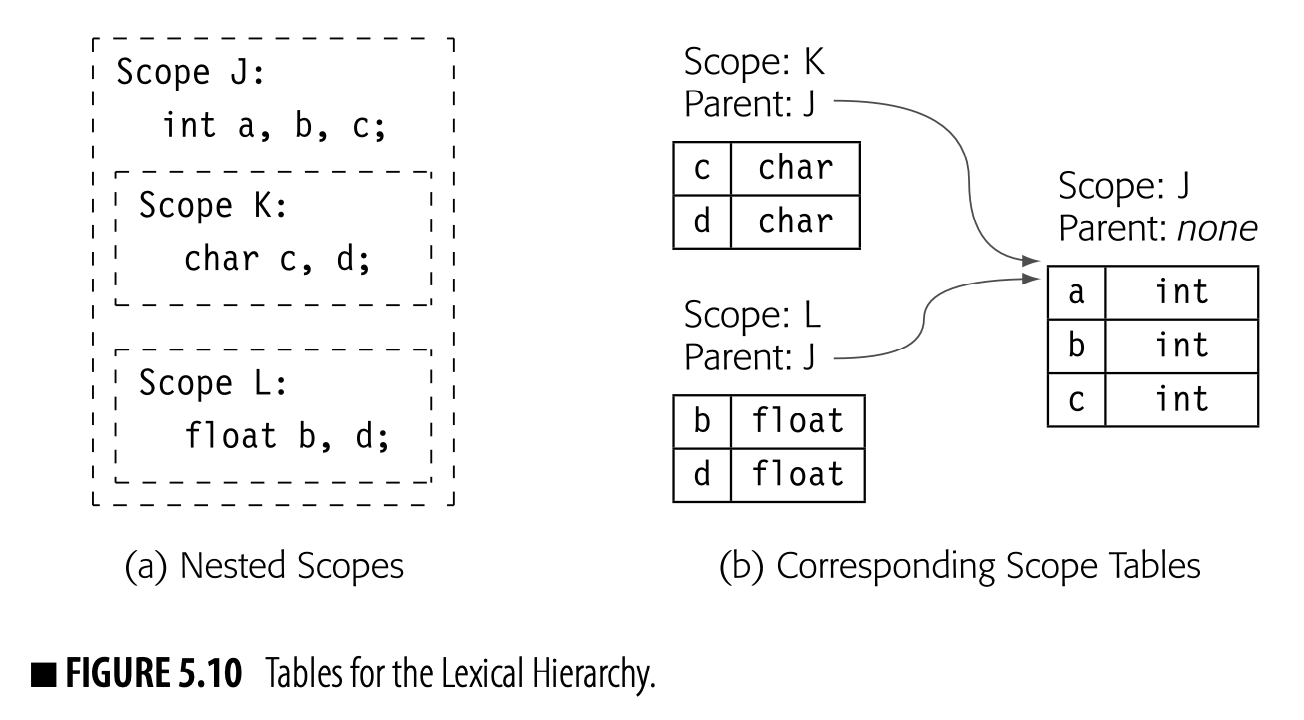

The compiler can build a separate table for each scope, as shown in Fig. 5.10. Panel (a) shows an outer scope that contains two inner scopes.

In scope K, a and b have type int while c and d have type char. In scope L, a and c have type int while b and d have type float.

In scope K, a and b have type int while c and d have type char. In scope L, a and c have type int while b and d have type float.

Scopes K and L are both nested inside scope J. Scopes K and L are otherwise unrelated.

Panel (b) shows the corresponding symbol tables. The table for a scope consists of both a hash table and a link to the surrounding scope. The gray arrows depict the search path, which reflects nesting in the code. Thus, a lookup of a in scope K would fail in the table for K, then follow the link to scope J, where it would find the definition of a as an int.

This approach lets the compiler create flexible, searchable models for the naming environment in each scope. A search path is just a list or chain of tables that specifies the order in which the tables will be searched. At compile time, a lookup for name resolution begins with the search path for the current scope and proceeds up the chain of surrounding scopes. Because the relationship between scopes is static (unchanging), the compiler can build scope-specific search paths with syntax-driven translation and preserve those tables and paths for use in later stages of the compiler and, if needed, in other tools.

Building the Model

The compiler writer can arrange to build the name-space model during syntax-driven translation. The source language constructs that enter and leave distinct scopes can trigger actions to create tables and search paths. The productions for declarations and references can create and refine the entries for names.

- Block Democations such as begin and end, , and procedure entry and exit, create a new table on entry to the scope and link it to the start of the search path for the block(s) associated with the current scope. On exit, the action should mark the table as final.

DYNAMIC SCOPING

The alternative to lexical scoping is dynamic scoping. The distinction between lexical and dynamic scoping only matters when a procedure refers to a variable that is declared outside the procedure’s own scope, sometimes called a free variable.

With lexical scoping, the rule is simple and consistent: a free variable is bound to the declaration for its name that is lexically closest to the use. If the compiler starts in the scope containing the use, and checks successive surrounding scopes, the variable is bound to the first declaration that it finds. The declaration always comes from a scope that encloses the reference.

With dynamic scoping, the rule is equally simple: a free variable is bound to the variable by that name that was most recently created at runtime. Thus, when execution encounters a free variable, it binds that free variable to the most recent instance of that name. Early implementations created a runtime stack of names on which every name was pushed as its defining occurrence was encountered. To bind a free variable, the running code searched the name stack from its top downward until a variable with the right name was found. Later implementations are more efficient.

While many early Lisp systems used dynamic scoping, lexical scoping has become the dominant choice. Dynamic scoping is easy to implement in an interpreter and somewhat harder to implement efficiently in a compiler. It can create bugs that are difficult to detect and hard to understand. Dynamic scoping still appears in some languages; for example, Common Lisp still allows the program to specify dynamic scoping.

-

Variable Declarations, if they exist, create entries for the declared names in the local table and populate them with the declared attributes. If they do not exist, then attributes such as type must be inferred from references. Some size information might be inferred from points where aggregates are allocated.

-

References trigger a lookup along the search path for the current scope. In a language with declarations, failure to find a name in the local table causes a search through the entire search path. In a language without declarations, the reference may create a local entity with that name; it may refer to a name in a surrounding scope. The rules on implicit decla- rations are language specific. FORTRAN creates the name with default attributes based on the first letter of the name. C looks for it in surrounding scopes and declares an error if it is not found. PYTHON’s actions depend on whether the first occurrence of the name in a scope is a definition or a use.

Examples

Lexical scope rules are generally similar across different programming languages. However, language designers manage to insert surprising and idiosyncratic touches. The compiler writer must adapt the general translation schemes described here to the specific rules of the source language.

C has a simple, lexically scoped name space. Procedure names and global variables exist in the global scope. Each procedure creates its own local scope for variables, parameters, and labels. C does not include nested procedures or functions, although some compilers, such as GCC, implement this extension. Blocks, set off by , create their own local scopes; blocks can be nested.

The C keyword static both restricts a name's visibility and specifies its lifetime. A static global name is only visible inside the file that contains its declaration. A static local name has local visibility. Any static name has a global lifetime; that is, it retains its value across distinct invocations of the declaring procedure.

SCHEME has scope rules that are similar to those in C. Almost all entities in SCHEME reside in a single global scope. Entities can be data; they can be executable expressions. System-provided functions, such as cons, live alongside user-written code and data items. Code, which consists of an executable expression, can create private objects by using a let expression. Nesting 1et expressions inside one another can create nested lexical scopes of arbitrary depth.

PYTHON is an Algol-like language that eschews declarations. It supports three kinds of scopes: a local function-specific scope for names defined in a function; a global scope for names defined outside of any programmer-supplied function; and a builtin scope for implementation-provided names such as print. These scopes nest in that order: local embeds in global which embeds in builtin. Functions themselves can nest, creating a hierarchy of local scopes.

PYTHON does not provide type declarations. The first use of a name in a scope is its defining occurrence. If the first use assigns a value, then it binds to a new local entity with its type defined by the assigned value. If the first use refers to 's value, then it binds to a global entity; if no such entity exists, then that defining use creates the entity. If the programmer intends to be global but needs to define it before using it, the programmer can add a nonlocal declaration for the name, which ensures that is in the global scope.

TERMINOLOGY FOR OBJECT-ORIENTED LANGUAGES

The diversity of object-oriented languages has led to some ambiguity in the terms that we use to discuss them. To make the discussion in this chapter concrete, we will use the following terms: Object An object is an abstraction with one or more members. Those members can be data items, code that manipulates those data items, or other objects. An object with code members is a class. Each object has internal state-data whose lifetimes match the object's lifetime. Class A class is a collection of objects that all have the same abstract structure and characteristics. A class defines the set of data members in each instance of the class and defines the code members, or methods, that are local to that class. Some methods are public, or externally visible, while others are private, or invisible outside the class. Inheritance Inheritance is a relationship among classes that defines a partial order on the name scopes of classes. A class a may inherit members from its superclass. If a is the superclass of b, b is a subclass of a. A name x defined in a subclass obscures any definitions of x in a superclass. Some languages allow a class to inherit from multiple superclasses. Receiver Methods are invoked relative to some object, called the method's receiver. The receiver is known by a designated name inside the method, such as this or self.

The power of an arises, in large part, from the organizational possibilities presented by its multiple name spaces.

5.4.2 Inheritance Hierarchies

Object-oriented languages (OOLs) introduce a second form of nested name space through inheritance. OOLs introduce classes. A class consists of a collection (possibly empty) of objects that have the same structure and behavior. The class definition specifies the code and data members of an object in the class.

Polymorphism The ability of an entity to take on different types is often called polymorphism.

Much of the power of an OOL derives from the ability to create new classes by drawing on definitions of other existing classes. In JAVA terminology, a new class can extend an existing class ; objects of class then inherit definitions of code and data members from the definition of . may redefine names from with new meanings and types; the new definitions obscure earlier definitions in or its superclasses. Other languages provide similar functionality with a different vocabulary.

The terminology used to specify inheritance varies across languages. In JAVA, a subclass extends its superclass. In C++, a subclass is derived from its superclass.

Subtype polymorphism the ability of a subclass object to reference superclass members

Class extension creates an inheritance hierarchy: if is the superclass of , then any method defined in must operate correctly on an object of class , provided that the method is visible in . The converse is not true. A subclass method may rely on subclass members that are not defined in instances of the superclass; such a method cannot operate correctly on an object that is an instance of the superclass.

In a single-inheritance language, such as JAVA, inheritance imposes a tree-structured hierarchy on the set of classes. Other languages allow a class to have multiple immediate superclasses. This notion of "multiple inheritance" gives the programmer an ability to reuse more code, but it creates a more complex name resolution environment.

Each class definition creates a new scope. Names of code and data members are specific to the class definition. Many languages provide an explicit mechanism to control the visibility of member names. In some languages, class definitions can contain other classes to create an internal lexical hierarchy. Inheritance defines a second search path based on the superclass relationship.

In translation, the compiler must map an pair back to a specific member declaration in a specific class definition. That binding provides the compiler with the type information and access method that it needs to translate the reference. The compiler finds the object name in the lexical hierarchy; that entry provides a class that serves as the starting point for the compiler to search for the member name in the inheritance hierarchy.

Modeling Inheritance Hierarchies

The lexical hierarchy reflects nesting in the syntax. The inheritance hierarchy is created by definitions, not syntactic position.

To resolve member names, the compiler needs a model of the inheritance hierarchy as defined by the set of class declarations. The compiler can build a distinct table for the scope associated with each class as it parses that class' declaration. Source-language phrases that establish inheritance cause the compiler to link class scopes together to form the hierarchy. In a single-inheritance language, the hierarchy has a tree structure; classes are children of their superclasses. In a multiple-inheritance language, the hierarchy forms an acyclic graph.

The compiler uses the same tools to model the inheritance hierarchy that it does to model the lexical hierarchy. It creates tables to model each scope. It links those tables together to create search paths. The order in which those searches occur depends on language-specific scope and inheritance rules. The underlying technology used to create and maintain the model does not.

Compile-Time Versus Runtime Resolution

Closed class structure If the class structure of an application is fixed at compile time, the OOL has a closed hierarchy.

The major complication that arises with some OOLs derives not from the presence of an inheritance hierarchy, but rather from when that hierarchy is defined. If the OOL requires that class definitions be present at compile time and that those definitions cannot change, then the compiler can resolve member names, perform appropriate type checking, determine appropriate access methods, and generate code for member-name references. We say that such a language has a closed class structure.

By contrast, if the language allows the running program to change its class structure, either by importing class definitions at runtime, as in JAVA, or by editing class definitions, as in SMALLtalk, then the language may need to defer some name resolution and binding to runtime. We say that such a language has an open class structure.

Lookup with Inheritance

Assume, for the moment, a closed class structure. Consider two distinct scenarios:

Qualified name a multipart name, such as

x.part, wherepartis an element of an aggregate entity namedx

- If the compiler finds a reference to an unqualified name in some procedure , it searches the lexical hierarchy for . If is a method defined in some class , then might also be a data member of or some superclass of ; thus, the compiler must insert part of the inheritance hierarchy into the appropriate point in the search path.

- If the compiler finds a reference to member of object , it first resolves in the lexical hierarchy to an instance of some class . Next, it searches for in the table for class ; if that search fails, it looks for in each table along 's chain of superclasses (in order). It either finds or exhausts the hierarchy.

One of the primary sources of opportunity for just-in-time compilers is lowering the costs associated with runtime name resolution.

With an open class structure, the compiler may need to generate code that causes some of this name resolution to occur at runtime, as occurs with a virtual function in C++. In general, runtime name resolution replaces a simple, often inexpensive, reference with a call to a more expensive runtime support routine that resolves the name and provides the appropriate access (read, write, or execute).

Building the Model

As the parser processes a class definition, it can (1) enter the class name into the current lexical scope and (2) create a new table for the names defined in the class. Since both the contents of the class and its inheritance context are specified with syntax, the compiler writer can use syntax-drivenactions to build and populate the table and to link it into the surrounding inheritance hierarchy. Member names are found in the inheritance hierarchy; unqualified names are found in the lexical hierarchy.

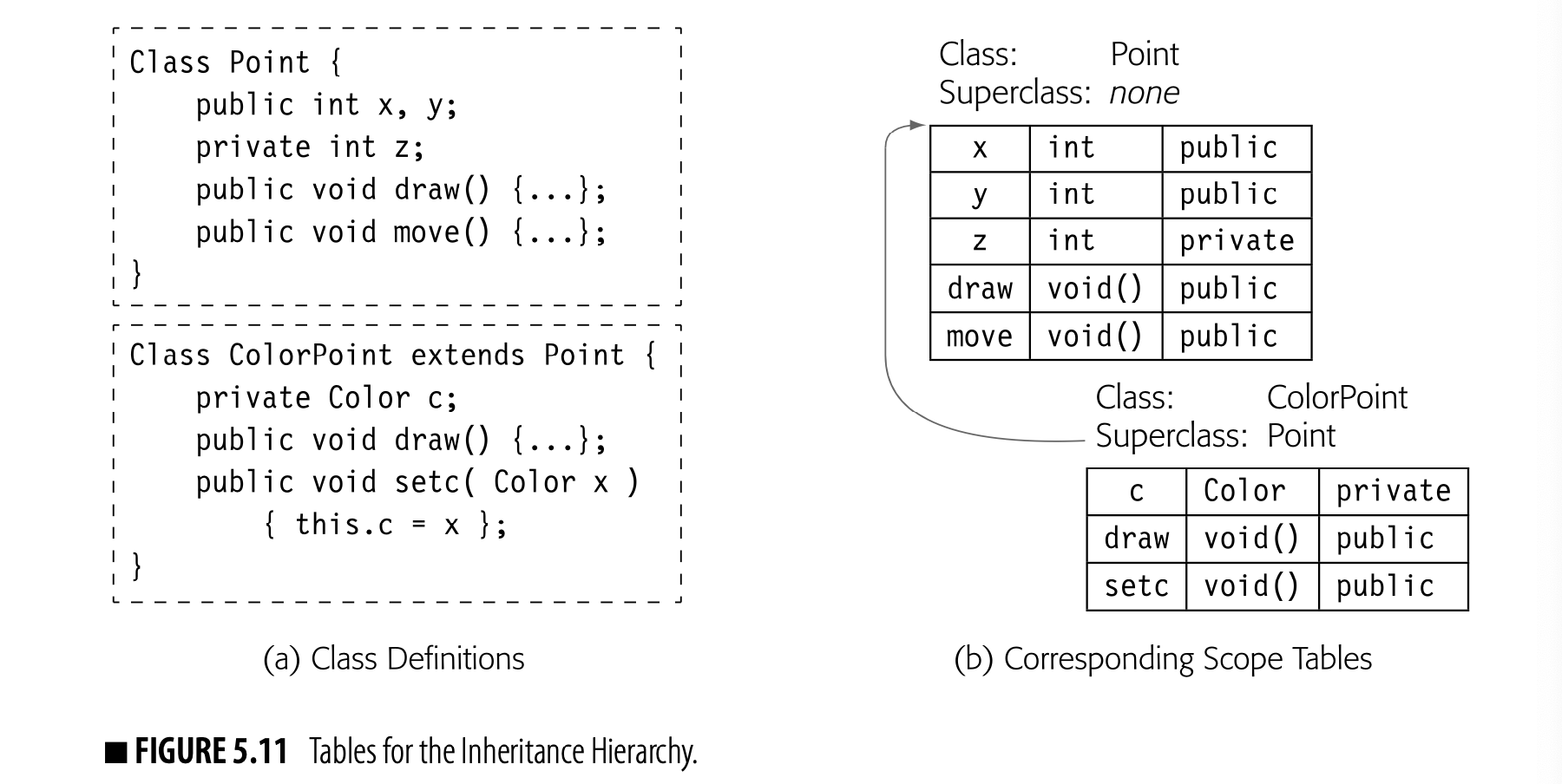

The compiler can use the symbol-table building blocks designed for lexical hierarchies to represent inheritance hierarchies. Fig. 5.11 shows two class definitions, one for Point and another for ColorPoint, which is a subclass of Point. The compiler can link these tables into a search path for the inheritance hierarchy, shown in the figure as a SuperClass pointer. More complicated situations, such as lexically nested class definitions, simply produce more complex search paths.

The compiler can use the symbol-table building blocks designed for lexical hierarchies to represent inheritance hierarchies. Fig. 5.11 shows two class definitions, one for Point and another for ColorPoint, which is a subclass of Point. The compiler can link these tables into a search path for the inheritance hierarchy, shown in the figure as a SuperClass pointer. More complicated situations, such as lexically nested class definitions, simply produce more complex search paths.

Examples

Object-oriented languages differ in the vocabulary that they use and in the object-models that they use.

C++ has a closed class structure. By design, method names can be bound to implementations at compile time. C++ includes an explicit declaration to force runtime binding--the C++ virtual function.

By contrast, JAVA has an open class structure, although the cost of changing the class structure is high--the code must invoke the class loader to import new class definitions. A compiler could, in principle, resolve method names to implementations at startup and rebind after each invocation of the class loader. In practice, most JAVA systems interpret bytecode and compile frequently executed methods with a just-in-time compiler. This approach allows high-quality code and late binding. If the class loader overwrites some class definition that was used in an earlier JIT-compilation, it can force recompilation by invalidating the code for affected methods.

Multiple Inheritance

Multiple inheritance a feature that allows a class to inherit from multiple immediate superclasses

Some OOLs allow multiple inheritance. The language needs syntax that lets a programmer specify that members , , and inherit their definitions from superclass while members and inherit their definitions from superclass . The language must resolve or prohibit nonsensical situations, such as a class that inherits multiple definitions of the same name.

To support multiple inheritance, the compiler needs a more complex model of the inheritance hierarchy. It can, however, build an appropriate model from the same building blocks: symbol tables and explicit search paths. The complexity largely manifests itself in the search paths.

5.4.3 Visibility

Visibility A name is visible at point p if it can be referenced at p. Some languages provide ways to control a name’s visibility.

Programming languages often provide explicit control over visibility--that is, where in the code a name can be defined or used. For example, C provides limited visibility control with the static keyword. Visibility control arises in both lexical and inheritance hierarchies.

C's static keyword specifies both lifetime and visibility. A C static variable has a lifetime of the entire execution and its visibility is restricted to the current scope and any scopes nested inside the current scope. With a declaration outside of any procedure, static limits visibility to code within that file. (Without static, such a name would be visible throughout the program.)

For a C static variable declared inside a procedure, the lifetime attribute of static ensures that its value is preserved across invocations. The visibility attribute of static has no effect, since the variable's visibility was already limited to the declaring procedure and any scopes nested inside it.

JAVA provides explicit control over visibility via the keywords public, private, protected, and default.

- public A public method or data member is visible from anywhere in the program.

- private A private method or data member is only visible within the class that encloses it.

- protected A protected method or data member is visible within the class that encloses it, in any other class declared in the same package, and in any subclass declared in a different package.

- default A default method or data member is visible within the class that encloses it and in any other class declared in the same package. If no visibility is specified, the object has default visibility.

Neither private nor protected can be used on a declaration at the top level of the hierarchy because they define visibility with respect to the enclosing class; at the top level, a declaration has no enclosing class.

As the compiler builds the naming environment, it must encode the visibility attributes into the name-space model. A typical implementation will include a visibility tag in the symbol table record of each name. Those tags are consulted in symbol table lookups.

As mentioned before, PYTHON determines a variable's visibility based on whether its defining occurrence is a definition or a use. (A use implies that the name is global.) For objects, PYTHON provides no mechanism to control visibility of their data and code members. All attributes (data members) and methods have global visibility.

5.4.4 Performing Compile-Time Name Resolution

During translation, the compiler often maps a name's lexeme to a specific entity, such as a variable, object, or procedure. To resolve a name's identity, the compiler uses the symbol tables that it has built to represent the lexical and inheritance hierarchies. Language rules specify a search path through these tables. The compiler starts at the innermost level of the search path. It performs a lookup on each table in the path until it either finds the name or fails in the outermost table.

The specifics of the path are language dependent. If the syntax of the name indicates that it is an object-relative reference, then the compiler can start with the table for the object's class and work its way up the inheritance hierarchy. If the syntax of the name indicates that it is an "ordinary" program variable, then the compiler can start with the table for the scope in which the reference appears and work its way up the lexical hierarchy. If the language's syntax fails to distinguish between data members of objects and ordinary variables, then the compiler must build some hybrid search path that combines tables in a way that models the language-specified scope rules.

The compiler can maintain the necessary search paths with syntax-driven actions that execute as the parser enters and leaves scopes, and as it enters and leaves declarations of classes, structures, and other aggregates. The details, of course, will depend heavily on the specific rules in the source language being compiled.

SECTION REVIEW

Programming languages provide mechanisms to control the lifetime and visibility of a name. Declarations allow explicit specification of a name’s properties. The placement of a declaration in the code has a direct effect on lifetime and visibility, as defined by the language’s scope rules. In an object-oriented language, the inheritance environment also affects the properties of a named entity.

To model these complex naming environments, compilers use two fundamental tools: symbol tables and search paths that link tables together in a hierarchical fashion. The compiler can use these tools to construct context-specific search spaces that model the source-language rules.

REVIEW QUESTIONS

- Assume that the compiler builds a distinct symbol table and search path for each scope. For a simple PASCAL-like language, what actions should the parser take on entry to and exit from each scope?

- Using the table and search path model for name resolution, what is the asymptotic cost of (a) resolving a local name? (b) resolving a nonlocal name? (Assume that table lookup has a cost.) In programs that you have written, how deeply have you nested scopes?

5.5 Type Information

Type an abstract category that specifies properties held in common by all members of the type Common types include integer, character, list, and function.

In order to translate references into access methods, the compiler must know what the name represents. A source language name fee might be a small integer; it might be a function of two character strings that returns a floating-point number; it might be an object of class fum. Before the front end can emit code to manipulate fee, it must know fee's fundamental properties, summarized as its type.

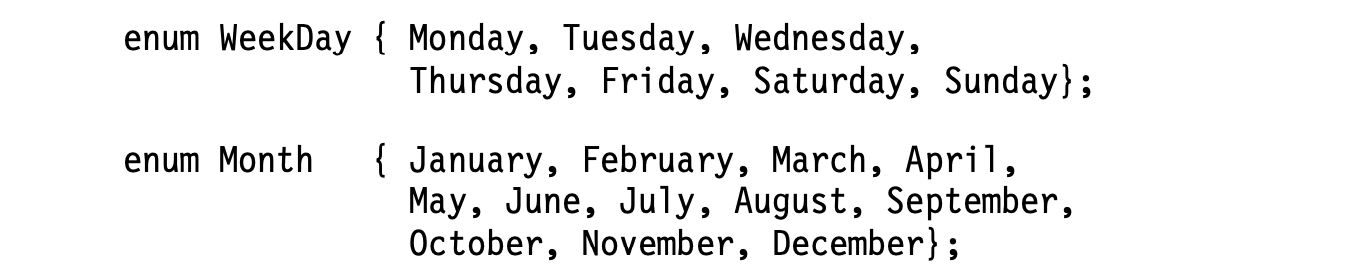

A type is just a collection of properties; all members of the type have the same properties. For example, an integer might be defined as any whole number in the range , or red might be a value in the enumerated type colors defined as the set .

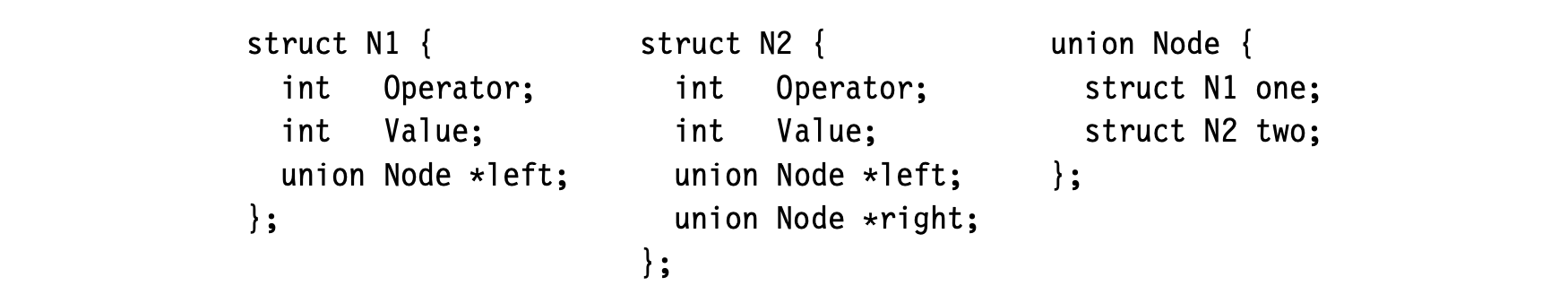

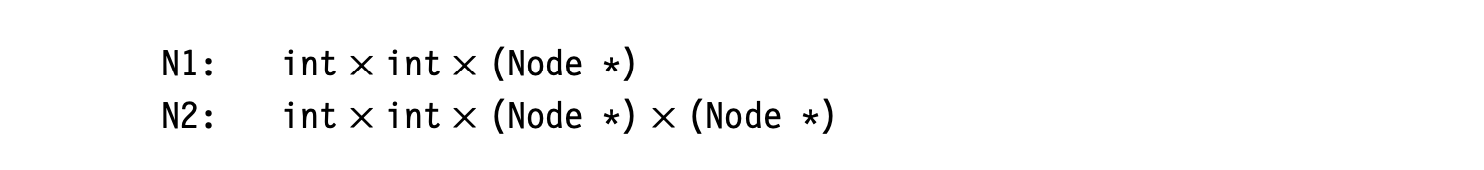

We represent the type of a structure as the product of the types of its constituent fields, in order.

Types can be specified by rules; for example, the declaration of a structure in C defines a type. The structure's type specifies the set of declared fields and their order inside the structure; each field has its own type that specifies its interpretation. Programming languages predefine some types, called base_types. Most languages allow the programmer to construct new types. The set of types in a given language, along with the rules that use types to specify program behavior, are collectively called a type system.

The type system allows both language designers and programmers to specify program behavior at a more precise level than is possible with a context-free grammar. The type system creates a second vocabulary for describing the behavior of valid programs. Consider, for example, the JAVA expression a+b. The meaning of + depends on the types of a and b. If a and b are strings, the + operator specifies concatenation. If a and b are numbers, the + operator specifies addition, perhaps with implicit conversion to a common type. This kind of overloading requires accurate type information.

5.5.1 Uses for Types in Translation

Types play a critical role in translation because they help the compiler understand the meaning and, thus, the implementation of the source code. This knowledge, which is deeper than syntax, allows the compiler to detect errors that might otherwise arise at runtime. In many cases, it also lets the compiler generate more efficient code than would be possible without the type information.

Conformable We will say that an operator and its operands are conformable if the result of applying the operator to those arguments is well defined.

The compiler can use type information to ensure that operators and operands are conformable--that is, that the operator is well defined over the operands' types (e.g., string concatenation might not be defined over real numbers). In some cases, the language may require the compiler to insert code to convert nonconformable arguments to conformable types--a process called implicit conversion. In other cases (e.g., using a floating-point number as a pointer), the language definition may disallow such conversion; the compiler should, at a minimum, emit an informative error message to give the programmer insight into the problem.

If x is real but provably 2, there are less expensive ways to compute ax than with a Taylor series.

Type information can lead the compiler to translations that execute efficiently. For example, in the expression , the types of and determine how best to evaluate the expression. If is a nonnegative integer, the compiler can generate a series of multiplications to evaluate . If, instead, is a real number or a negative number, the compiler may need to generate code that uses a more complex evaluation scheme, such as a Taylor-series expansion. (The more complicated form might be implemented via a call to a support library.) Similarly, languages that allow whole structure or whole array assignment rely on conformability checking to let the compiler implement these constructs in an efficient way.

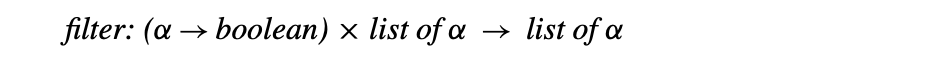

Type signature a specification of the types of the formal parameters and return value(s) of a function

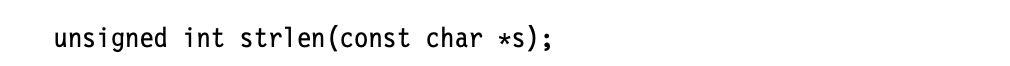

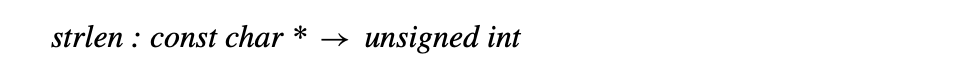

Function prototype The C language includes a provision that lets the programmer declare functions that are not present. The programmer includes a skeleton declaration, called a function prototype.

At a larger scale, type information plays an important enabling role in modular programming and separate compilation. Modular programming creates the opportunity for a programmer to mis-specify the number and types of arguments to a function that is implemented in another file or module. If the language requires that the programmer provide a type signature for any externally defined function (essentially, a C function prototype), then the compiler can check the actual arguments against the type signature.

Type information also plays a key role in garbage collection (see Section 6.6.2). It allows the runtime collector to understand the size of each entity on the heap and to understand which fields in the object are pointers to other, possibly heap-allocated, entities. Without type information, collected at compile time and preserved for the collector, the collector would need to conservatively assume that any field might be a pointer and apply runtime range and alignment tests to exclude out-of-bounds values.

Lack of Type Information

Complete type information might be un- available due to language design or due to late binding.

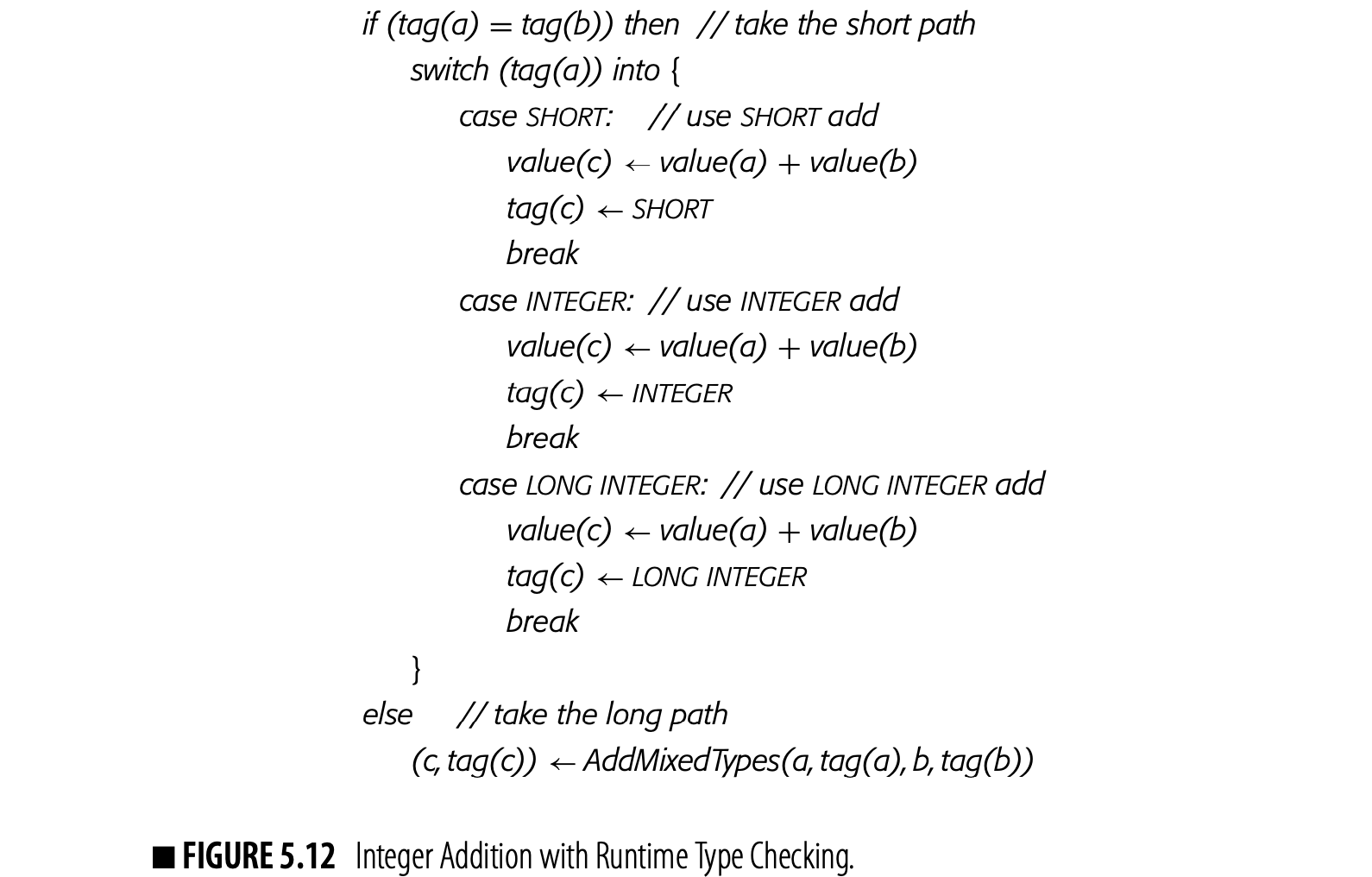

If type information is not available during translation, the compiler may need to emit code that performs type checking and code selection at runtime. Each entity of unknown type would need a runtime tag to hold its type. Instead of emitting a simple operator, the compiler would need to generate case logic based on the operand types, both to perform tag generation and to manipulate the values and tags.

Fig. 5.12 uses pseudocode to show what the compiler might generate for addition with runtime checking and conversion. It assumes three types, SHORT, INTEGER, and LONG INTEGER. If the operands have the same type, the code selects the appropriate version of the addition operator, performs the arithmetic, and sets the tag. If the operands have distinct types, it invokes a library routine that performs the complete case analysis, converts operands appropriately, adds the converted operands, and returns the result and its tag.

By contrast, of course, if the compiler had complete and accurate type information, it could generate code to perform both the operation and any necessary conversions directly. In that situation, runtime tags and the associated tag-checking would be unnecessary.

5.5.2 Components of a Type System

A type system has four major components: a set of base types, or built-in types; rules to build new types from existing types; a method to determine if two types are equivalent; and rules to infer the type of a source-language expression.

Base Types

The size of a “word” may vary across im- plementations and processors.

Most languages include base types for some, if not all, of the following kinds of data: numbers, characters, and booleans. Most processors provide direct support for these kinds of data, as well. Numbers typically come in several formats, such as integer and floating point, and multiple sizes, such as byte, word, double word, and quadruple word.

Individual languages add other base types. LISP includes both a rational number type and a recursive-list type. Rational numbers are, essentially, pairs of integers interpreted as a ratio. A list is either the designated value nil or a list built with the constructor cons; the expression (cons first rest) is an ordered list where first is an object and rest is a list.

Languages differ in their base types and the operators defined over those base types. For example, C and C++ have many varieties of integers; long int and unsigned long int have the same length, but support different ranges of integers. PYTHON has multiple string classes that provide a broad set of operations; by contrast, C has no string type so programmers use arrays of characters instead. C provides a pointer type to hold an arbitrary memory address; JAVA provides a more restrictive model of reference types.

Compound and Constructed Types

Some languages provide higher-level abstractions as base types, such as PYTHON maps.

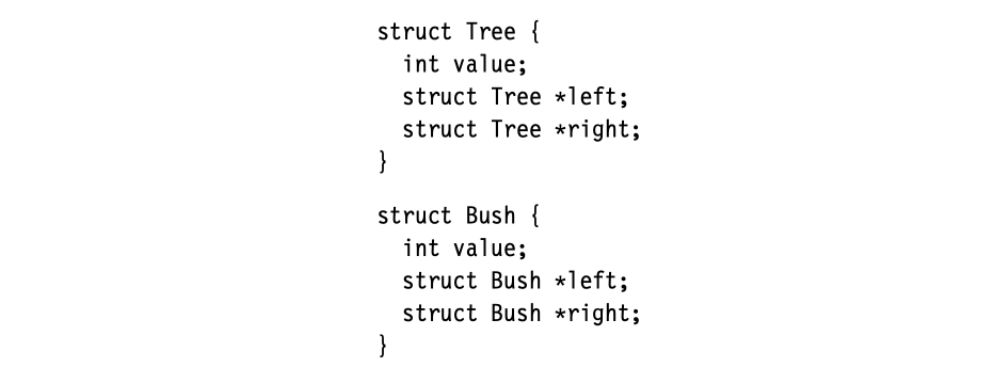

The base types of a programming language provide an abstraction for the actual kinds of data supported by the processor. However, the base types are often inadequate to represent the information domain that the programmer needs--abstractions such as graphs, trees, tables, records, objects, classes, lists, stacks, and maps. These higher-level abstractions can be implemented as collections of multiple entities, each with its own type.

In an OOL, classes can be treated as con- structed types. Inheritance defines a subtype relationship, or specialization.

The ability to construct new types to represent compound or aggregate objects is an essential feature of many languages. Typical constructed types include arrays, strings, enumerated types, and structures or records. Compound types let the programmer organize information in novel, program-specific ways. Constructed types allow the language to express higher-level operations, such as whole-structure assignment. They also improve the compiler's ability to detect ill-formed programs.

Arrays

Arrays are among the most widely used aggregate objects. An array groups together multiple objects of the same type and gives each a distinct name--albeit an implicit, computed name rather than an explicit, programmer-designated name. The C declaration int a[100][200]; sets aside space for ,000 integers and ensures that they can be addressed using the name a. The references a[1][17] and a[2][30] access distinct and independent memory locations. The essential property of an array is that the program can compute names for each of its elements by using numbers (or some other ordered, discrete type) as subscripts.

Array conformability Two arrays a and b are conformable with respect to some array operator if the di- mensions of a and b make sense with the operator. Matrix multiply, for example, imposes different conformability requirements than does matrix addition.

Support for operations on arrays varies widely. FORTRAN 90, PL/I, and apl all support assignment of whole or partial arrays. These languages support element-by-element application of arithmetic operations to arrays. For conformable arrays x, y, and z, the statement would overwrite each x[i,j] with y[i,j]+z[i,j]. Apl takes the notion of array operations further than most languages; it includes operators for inner product, outer product, and several kinds of reductions. For example, the sum reduction of y, written , assigns x the scalar sum of the elements of y.